It’s small, this little welt on my hand or the bump behind my ear. The welts come and go and are a minor annoyance during the spring, summer and fall when I am gardening or when my husband and I host outside gatherings or when the grandchildren come to play and explore the path through the woods their grandfather cut for them. These seasons are when mosquitoes buzz in the air and wait to strike humans for the blood the females need to nourish their eggs.

Feeding on a human arm, this Anopheles albimanus mosquito is a vector of malaria, so mosquito control is critically important for reducing the incidence of malaria.

Photo by James Gathany, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

It is a little distraction; I bat away the pesky critter or slap it when it sucks my blood, causing a splat on my own skin. The bump caused by this bite swells and itches, but I’ve learned the more I scratch, the itchier the welt becomes.

When a mosquito bite breaks the skin, my immune system sets off a warning; the mini-wound is instantly flushed with increased blood flow and my white-blood-cell count elevates slightly. This reaction causes the swelling; it is really an allergic reaction. On the micro-scale of things, this physiological response is instantaneous. For most of us, a mosquito bite, or multiple bites, is an annoyance causing us to itch, then scratch, and finally, if the bites continue to annoy, seek some kind of salve to soothe and a repellant to prevent.

In some places in the world, however, a mosquito is no small thing. It can bring on fevers, illnesses, work displacement and even death—causing thousands of families sorrow.

In my original special report for Gospel for Asia titled It Takes Only One Mosquito, I explored the impact of faith based organizations on modern medical approaches. This update explores the ancient and ongoing battle between man and mosquitos which transmit vector-borne diseases.

Malawi: Education on malaria prevention can be taught in schools as children participate in a class on malaria and how to protect themselves. Photo by WHO / S. Hollyman

Know Your Enemy or Yield to Vector-borne Diseases

Knowing your enemy is well-known advice attributed to Sun Tzu’s ancient Asian manual The Art of War, which is part of a syllabus for potential military-service candidates. Its recommendation for warriors is certainly appropriate for the equally ancient conflict that exists in many parts of the world between Man and Mosquito. In reality, where I live the welt on my hand may be small and annoying but for whole population sectors around the world, the negative impact of mosquitoes and the diseases they may transmit is overwhelmingly huge.

So let’s take Sun Tzu’s advice and get to know our enemy:

There are more than

3,000 species

of mosquitoes in the world.

About

175 species

can be found in the U.S.

The most common, and most dangerous, are the various species in the Culex, Anopheles and Aedes2

Mosquitoes can live in almost any environment, with the exception of extreme cold. They favor forests, marshes, tall-grass and locales, and ground that is wet at least part of the year. Incredibly, Arctic tundra is a great breeding-place for mosquitoes—the soil that has been frozen all winter thaws in the warming weather, rendering these vast acres huge mosquito incubators. These insects must have water to survive (breeding can occur in as little as one inch of standing water), so areas that border ponds, lakes or puddles are essential to their spread and survival.

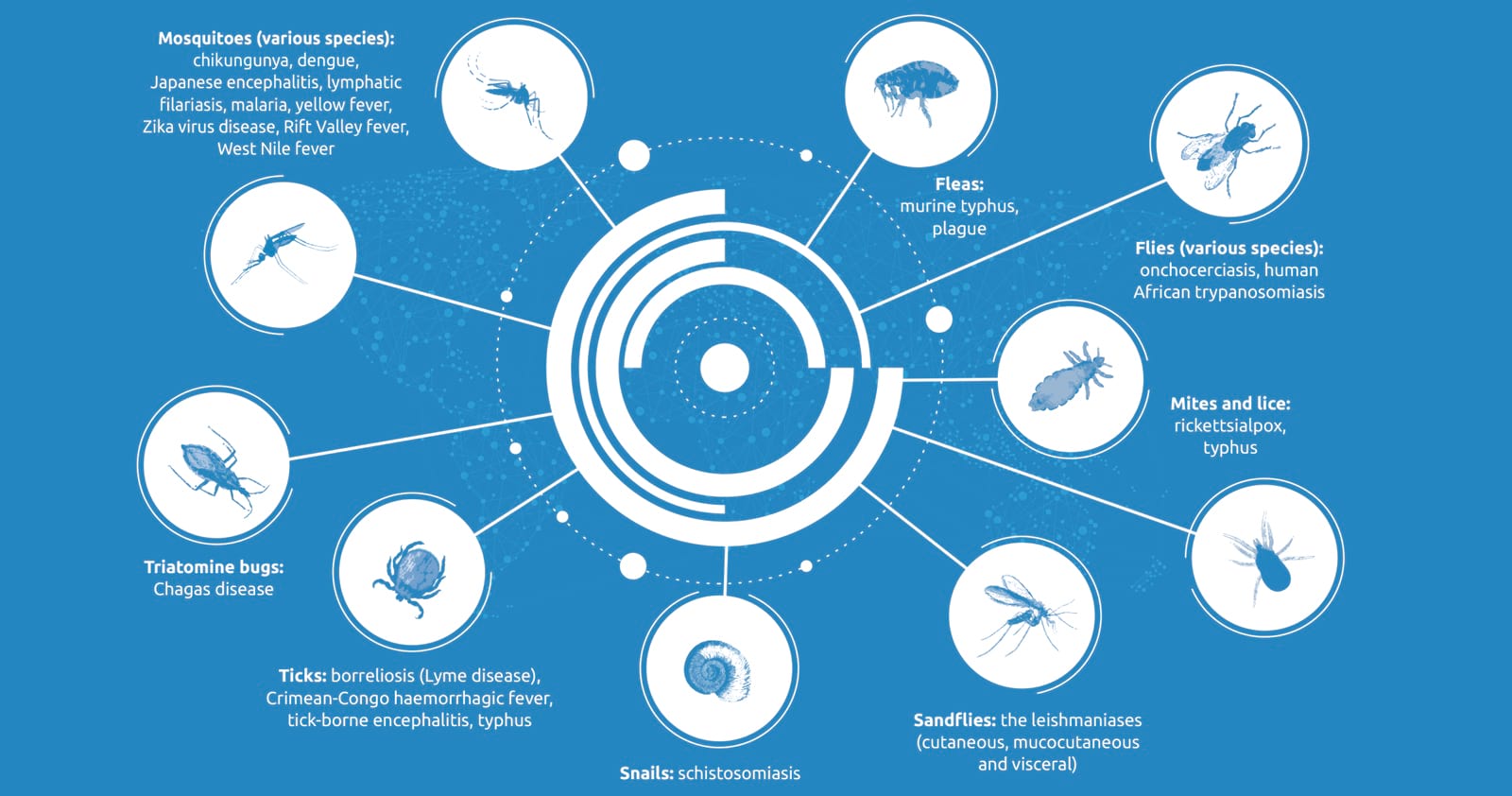

Categorized among the group known as “blood-feeding arthropods” which also includes ticks and fleas, mosquitoes are responsible for a wide range of diseases that result in various symptoms such as fevers, rashes, aches and pains, vomiting and death. The World Health Organization classifies such illnesses as “vector-borne diseases,” which are “human illnesses caused by parasites, viruses and bacteria that are transmitted by vectors.”3

The WHO’s report on vector-borne diseases includes these stunning facts:

Vector-borne diseases account for more than 17 percent of all infectious diseases, causing more than 700,000 deaths annually.

Malaria is a parasitic infection transmitted by Anopheline It causes an estimated 219 million cases globally and results in more than 400,000 deaths every year. Most of the deaths occur in children under the age of 5 years.

Dengue is the most prevalent viral infection transmitted by Aedes More than 3.9 billion people in more than 129 countries are at risk of contracting dengue, with an estimated 96 million symptomatic cases and an estimated 40,000 deaths every year.

“Other diseases transmitted by vectors include chikungunya, Zika, yellow fever, West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis (all transmitted by mosquitoes) and tick-borne encephalitis (transmitted by ticks).”4

Other Odd Facts in the War on Mosquitoes

Zika virus, which has caused thousands of infants in Brazil alone to be born with abnormally small heads and neurological problems, joins a suite of emerging and long-established diseases transmitted throughout the world by mosquitoes. The actual disease-causing agents are the viruses, bacteria or parasites that the mosquitoes pick up when they feed on the blood of an infected person or animal. Photo by UC Davis

These vectors can transmit infectious pathogens between humans, or from animal to humans. Mosquitoes, as mentioned, are blood-sucking insects; when doing so, they can ingest pathogens from a host and transfer it to another host once that pathogen begins to replicate. Often, once a vector becomes infected, it is capable of transmitting the pathogen for the rest of its life, becoming a flying, one-insect, disease-delivery machine.

According to the WHO, 700,000 people die each year from malaria, dengue, Japanese encephalitis and other vector-borne diseases.

“The burden of these diseases is highest in tropical and subtropical areas, and they disproportionately affect the poorest populations,” writes the WHO.

Photo by WHO/HTM/GVCR/2017.01 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO)

“Since 2014, major outbreaks of dengue, malaria, chikungunya, yellow fever and Zika have afflicted populations, claimed lives, and overwhelmed health systems in many other countries. Other [vector-borne] diseases … cause chronic suffering, life-long morbidity, disability and occasional stigmatization.”5

Perhaps that little bump growing on my hand after a summer mosquito attack is not such a little thing after all.

This woman and her child in Uttar Pradesh, India, can function without fear of insect bites during the day, as well as sleep safely each night, due to the protective mosquito net they received as a Christmas gift from GFA World.

Mosquito Abatement: Part of Caring for the Least of These

Mosquitos are so dangerous because a single bite can transmit malaria or other parasitic diseases. This boy in South Asia is seen riding home with a new mosquito nets that he was given through a GFA World gift distribution. These nets are simple, cost-effective solutions to keep families safe from malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

In light of what we know now about that enemy, the mosquito, is it any wonder that mosquito-abatement programs sponsored by faith-based organizations like GFA World are one of the evidences that fulfill this Gospel imperative: “Love your neighbor as yourself”?

I love the story on GFA’s website reporting how GFA workers distributed some 9,000 mosquito nets to students living in hostels, now away from their families. Two nets were given to each student, one for them to use and one to send back home.

“I am thankful for the mosquito net,” said Marcus, a ninth-grade student. “I am from a poor family, and there is no one to meet my needs.”

On a broader scale, GFA World has delivered nets to thousands of families in need and held awareness training and awareness programs in many affected areas. In Odisha, a state greatly affected by various vector-borne , GFA workers led mosquito awareness programs and gave nets to 2,050 impoverished families, including people at a district medical hospital. In the tea-growing state of Assam, GFA workers conducted awareness training about the need for prevention, distributing 2,000 nets to tea-garden employees.6

To date, GFA World has distributed more than 1,300,000 mosquito nets in malaria-prone areas of South Asia to protect people from life-ending vector-borne diseases.

In some places in the world, a mosquito is no small thing.

It can bring on fevers, illnesses, work displacement and even death—causing thousands of families sorrow.

The world’s largest grassroots campaign to protect people from malaria is the United Nations Foundation’s Nothing But Nets campaign. Aiming to be the generation that defeats malaria, Nothing But Nets brings together UN partners, advocates and organizations worldwide to raise awareness, funds and voices to protect vulnerable families from malaria, given that every two minutes a child dies from malaria.7

Mosquito nets, as part of a general abatement program in many countries of the world, overcome one of the major deterrents to all of the above: the small, seemingly innocuous welt on the hand, behind the ear, on the ankle or calf. A mosquito bite.

National World Mosquito Day commemorates the discovery in 1897 by British doctor Sir Richard Ross that mosquitoes transmit malaria. GFA World workers hold a variety of events to distribute mosquito nets to guard against insect-borne diseases, including yellow fever, malaria, dengue and zika. These bednet recipients in South Asia smile with appreciation as they can now sleep without discomfort or fear of mosquito bites at night.

Other Means of Mosquito Warfare

Local and global management of mosquito-borne viruses, many without a vaccine to prevent or a cure to stop the progression of disease, must rely on preventive as well as palliative measures.

United Republic of Tanzania: A woman puts up a mosquito bednet to safeguard her family at night from mosquito bites.

Photo by WHO / S. Hollyman

First, there are protective measures individuals can practice while traveling to or living in mosquito-compromised territories. For instance, local home-dwellers can start by emptying any containers filled with water that are lying around the yard, house or apartment, or in alleys or garbage-collection centers. Tip over that plastic swimming pool and fill it again when needed. Dump any bowls outside that pets feed from. Some out-of-door containers can have holes punched in their bases so that water drains. Clean rain gutters so they don’t become clogged with leaves or debris, which inhibits rainwater from draining and leaves it to pool for days. These practices prevent mosquitoes from breeding in standing water.

Many of these abatement methods are a matter of paying attention and using common sense regarding standing-water sources. For instance, keep grass mowed, trim back bushes and rake up fallen leaves. These are all places where mosquitoes like to hide and breed. Some recommend that any low-lying depressions in a yard should be filled since they will hold water after lawn irrigation or rain. Swimming pools, of course, need to be kept clean and chlorinated. Stocking any small ponds with fish can deter mosquitoes, as fish eat mosquito larvae. As a last resort, for swarms of mosquitoes, spray insecticides.

This, of course, raises its own problems, since most foggers or sprays carry warnings in bold language on their labels. The possibility of unintentional user-poisoning from these highly lethal compounds is evidenced by the cautionary statements on them. For personal protection, a variety of DEET-free (diethyltoluamide) organic repellants are on the market. Many are safe to use around children. In our modern, chemical-wary society, various natural approaches to combating mosquito hoards are recommended, including growing plants that repel mosquitoes. The smell of marigolds, lavender, sage, rosemary and lemon Thai grass make them ideal candidates. A sprig of fresh rosemary placed in water for a few minutes and then placed on a hot grill is recommended as a natural repellant. In addition, pots of basil, bee-balm, catnip or citronella placed in patio or outside seating areas help reduce mosquito colonies.

For travelers, or people living in high at-risk areas like South Asia, a series of personal techniques can be utilized to combat the potential for mosquito bites. These include the following:

Get vaccinated for diseases like yellow fever and Japanese encephalitis. For all other mosquito-borne diseases, which do not have vaccines or medicines, the key strategy is to prevent mosquito bites.

Whenever possible, use insect repellant that’s approved as safe and effective.

Cover up with long-sleeved clothes and pants when you’re out and about, especially at dusk or night when you have the greatest risk, and avoid bright clothing.

Use window or door screens to keep mosquitoes out of your house.

Burn mosquito coils under your dinner table while sitting or eating outside.

Sleep under a mosquito net at night.

Photo by WHO/HTM/GVCR/2017.01 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO)

Since so many of South Asia’s poorest families cannot afford insect repellant, window screens or long-sleeved clothes, it becomes essential for non-profits like GFA World to provide the mosquito nets that will at least keep them safe at night.

Bednets only have to be changed once every 3-5 years. Here a fresh supply of mosquito nets is distributed to residents in Patang village, Cambodia. Photo by WHO / S. Hollyman

A Childhood Memory of the “Big Ditch”

Long ago, as a schoolgirl, I was assigned to read a book titled Mosquitoes in the Big Ditch. This is the historical account, in children’s literature, of the opening of the Panama Canal, which finally took place after great failure and much loss of life.

Ship passing through the new Agua Clara Locks, Panama Canal. Photo by Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Panama Canal cuts across the isthmus that joins Panama to Costa Rica at its north and to Colombia at its south. Before its engineering, ships needed to traverse around the southern coastline of South America, a lengthy journey by anyone’s measurement. The French had attempted to cut through this land mass and engineer the massive trench that would allow ships to cut their sailing route from east to west (or vice-versa) by thousands of miles. However, due to epidemics of malaria and primarily yellow fever, the French finally withdrew, and after two decades of hard labor and $287 million of investment, the canal project was terminated in 1889.

At this point, the United States bought the development rights to the Canal from the now-bankrupt French for a fraction of the cost. In the history of entomological transmission, the Americans were to succeed where many had failed because a handful of scientists proved yellow fever was caused through the transmission of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Before this discovery, the high incidence of infection was attributed to bad water, foul air and disastrous medical-care decisions that allowed the disease to spread.

William C. Gorgas

Photo by Wikimedia

U.S. Army physician Major Walter Reed finally demonstrated unequivocally that the vector for yellow fever was the Aedes aegypti. A newly-emerged mosquito was allowed to feed on a suffering patient and then bite volunteer coworkers. As predicted, they succumbed to yellow fever several days later. Mercifully, they recovered from the successful experiment.

In 1904, U.S. Chief Sanitary Officer Dr. William Gorgas took on the task of eradicating yellow-fever-carrying mosquitoes from the 500 square miles of jungle canal-zone. Some 4,000 workers, thousands of gallons of sprayed insecticide, 120 tons of pyrethrum insecticide powder, 300 tons of sulphur and 600,000 gallons of oil later, the task was done.8

It was to be the first of many thousands of such efforts, large and small, that would be conducted down through the decades since mosquitoes were defeated in the Big Ditch. It is a war, unfortunately, that needs to be won and won and won.

And while mosquitoes were momentarily defeated to construct the Big Ditch, the ancient war between man and mosquito still wages on every day in places like South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. And it takes “getting to know the enemy” to fulfill the task of eradicating vector-borne diseases, and protect people from life-ending mosquito bites.

You can help in this effort today by making a donation to provide mosquito nets to people in South Asia at risk of mosquito bites. Your gift of $50 will provide mosquito nets for five families in Asia, and safeguard them from the life-ending diseases that mosquitoes transmit.

The bump on my hand, in its conglomerate potential, is not so small after all.

This ends the update to our original Special Report,

which is featured in its entirety below.

It Takes Only One Mosquito(to lead to remarkable truths about faith-based organizations and world health)

It takes only one mosquito, buzzing around with ill intent, dive-bombing in the middle of the night, hovering ominously around a would-be sleeper’s ear, to cause alert wakefulness and ruin the REM-phase of deep slumber. Five or six mosquitoes, all in disharmonic buzzing in one room, demand that the sleepy occupants get up and destroy the pesky insects, no matter how many bug guts get left on the walls.

Interestingly, research about the ubiquitous presence of the mosquito led me to a startling discovery about the Gospel’s mostly unknown and stunning impact on the development of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) eight Millennium Development Goals. This is an article about that impact. Let me start at the beginning.

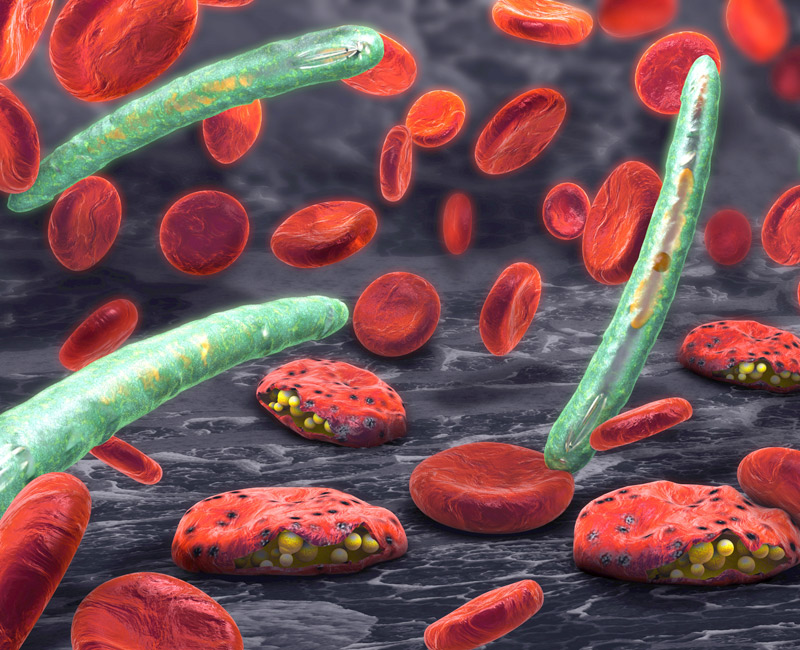

Malaria parasite (plasmodium)

By Christoph Burgstedt/Shutterstock.com

My son Jeremy, post-college and conveniently fluent in Spanish, was helping me with a writing project in Mexico thanks to some excess flight mileage points. Jeremy, at that time, was a counselor for World Relief, an international organization that assists churches to sponsor refugees. He had become proficient in dealing with immigration issues and consequently was open to being bribed by his mother to spend five work-and-play days on the Mexican Riviera.

One night, we returned to our room unaware the maid had neglected to close the screenless windows after cleaning. Finally resigned to the reality that hiding under the sheets was a futile deterrent against bloodthirsty pests, we turned on the lights and did battle royal, swinging towels and rolled-up manuscripts, until we were certain that not a single mosquito had survived the slaughter.

And yes, there were bug guts all over the walls.

I remember falling to sleep that night, deeply satisfied with our search-and-destroy mission, and suddenly catching myself thinking: What if this were a malaria-ridden country? It would only take one mosquito, the female anopheles, to transmit one of the parasites on the spectrum belonging to the genus Plasmodium. It only takes one mosquito bite in a person lacking immunity to bloom into rampant malaria some 10–15 days later.

A mosquito net can be the difference between life and death in some areas, protecting families from the bite of malaria-spreading mosquitos while they sleep.

Mosquitoes Nets Versus Malaria

It may seem strange in countries or communities that maintain sophisticated mosquito abatement programs to learn that mosquito nets across the world are one of the most important means of saving lives.

Stagnant water is a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes, endangering those living nearby.

GFA (SA) tells the story of Pastor Ojayit9 walking through villages and inquiring of residents as to whether they had been afflicted by malaria and if they needed mosquito nets. (These, for those who are unaware, are hung over beds, sleeping cots or hammocks at night.) The pastor was deeply moved by the numerous folk who had suffered with the mosquito-borne illness. One man named Madin, along with his family, had been ill with malaria and brain malaria on several occasions. Extreme poverty kept the family from affording medication or prevention treatments to combat the disease or the airborne insects that carried the disease.

Pastor Ojayit added Madin’s name to the list of recipients for the next GFA-supported Christmas gift distribution so he could receive a mosquito net. That simple gift meant, for the first time, Madin and his family began to thrive. The children could attend school; they all could gain back health. The gift of a mosquito net also demonstrated the practical application of God’s love and concern for the people of the world.

A mosquito net can be the difference between life and death—but the fight with malaria is far from over.

By Peteri/Shutterstock.com

The 2018 World Malaria Report indicated that in 2017, after an unprecedented period of early success stimulated by the World Health Organization’s campaign to bring malaria under global control, progress in fighting the disease has stalled. There were an estimated 219 million cases and 435,000 related deaths in 2017. This was up from 217 million cases in 2016.10 Evaluations as to the possible cause of this slide include a decrease of billions of donor dollars due to other disastrous disease episodes worldwide.

The report also added that 11 countries bear 70 percent of the burden of this particular global disease: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Uganda, Tanzania and India, most of them in tropical or subtropical areas of the world, most often where there are impoverished populations.11

Millennium Development Goals & Millennium Sustainable Development Goals

Despite this setback in malaria eradication, health indicators from around the world show that a handful of the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), introduced by the World Health Organization and announced in September 2000, are meeting or exceeding fulfillment expectations. The eight Millennium Development Goals are:

- to eradicate poverty and hunger;

- to achieve universal primary educations;

- to promote gender equality and empower women;

- to reduce child mortality;

- to improve maternal health;

- to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases;

- to ensure environmental sustainability; and

- to develop a global partnership for development.

The eight Millenium Development Goals. Photo by Kjerish on Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 4.0

The WHO Declaration notes that the “MDGs are inter-dependent; all the MDGs influence health, and health influences all the MDGs. For example, better health enables children to learn and adults to learn. Gender equality is essential to the achievement of better health. Reducing poverty, hunger and environmental degradation positively influences, but also depends on, better health.”12

So how is the world doing?

Despite the United Nations declaring this international effort “the most successful anti-poverty movement in history,” success is also a much more daunting task than the optimistic planners imagined. Since 2015, the MDGs morphed into the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals with 17 points and a more realistic target accomplishment date of 2030.

And why is that? Well, it’s just plain difficult to create a peaceable, equitable, egalitarian world system that dignifies the life of every human on the planet. Huge progress has been made in four out of the eight MDGs; extreme poverty levels, for instance, have been almost halved globally. Gender disparity goals in education were nearly met, new HIV infection levels were reduced by 40 percent and the world did reach the goal on access to safe drinking water13. However, unprecedented weather crises, rising conflict causing unanticipated migration patterns, the lack of high-level technology in many places for data gathering and more defeated the optimistic intents of the planner.

Photo by Grimpeurgf on Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 4.0

With all this as a background, now let’s focus on Millennium Development Goal #8, “to develop a global partnership for development.”

How have faith-based organizations impacted health initiatives in the modern era? The backstory to these simple seven words in goal #8 contains an excellent, if not elegant, example of the interaction of faith-based theology and compassionate intent on the policy-making behind the World Health Organization’s vital Declaration, which many world-watchers consider a watershed in the history of international development. This is a story that needs to be told and understood because it provides a map to effectuate more positive results to a world in crisis.

Faith-Based Organizations as Seen Through the Bite of the Mosquito

Let’s look at that mosquito again, the anopheles that carries some form of the genus Plasmodium, which is the genesis of several strains of potentially deadly malaria parasites. In addition to malaria, the bite of various mosquitoes can also transmit dengue and yellow fever as well as the Zika, West Nile and African Sleeping Sickness viruses. The long battle against the lone mosquito multiplied by millions of its kind presents a simulacrum through which an enormous topic—modern medicine outreaches as influenced by faith—can be viewed.

600,000

mosquito nets distributed in 2016 by GFA-supported workers

One of the specific health ministries GFA (SA) initiated in 2016 was to participate in World Mosquito Day, observed every August 20 to raise awareness about the deadly impact of mosquitoes. This global initiative encourages local governments to help control malaria outbreaks, and it also raises funds from large donor organizations and national governments to underwrite worldwide eradication efforts. Discovering and applying means of mosquito control in overpopulated areas of the world is essential, but the task is so large and the enemy so canny that planners have discovered they must rely on a combination of efforts that activate local communities and the leaders in those communities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), faith-based organizations (FBOs) and faith-based development organizations (FBDOs).

At a GFA-supported gift distribution, these villagers were grateful to receive a mosquito net.

In 2016, workers collaborating with GFA distributed some 600,000 mosquito nets, many of which were given to people living in districts where there are high malaria risks and high poverty levels. Due to poverty, these folks were unable to procure the simplest of means to prevent mosquito-borne diseases. In addition to the nets, which were given away without charge, GFA conducted disease-awareness training in order to heighten understanding about preventive measures.14

In the majority of rural areas, there are no clinics, no hospitals, no medical professionals and no treatment protocols.

This effort was compatible with the movement back to a primary health care emphasis as delineated in the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration15 encouraged by the World Health Organization, which proclaimed the principles of what was meant by the concept of primary health care and the overreaching need for it. While a few populations in developing countries have access to tertiary health care—hospitals and clinics and professionals trained in medical schools, drugs and diagnostic equipment—the vast majority of the rest of the populace can access extremely limited or next-to-no available health care. In the majority of rural areas, for instance, there are no clinics, no hospitals, no medical professionals and no treatment protocols. (This medical desert is also becoming a problem in the United States; as rural populations shrink, hospitals and clinics cannot afford to stay open.)

The Alma-Ata conference recommended a redirection of approaches to what is termed primary health care. Charles Elliott, an Anglican priest and development economist, summarized the suggested changes as follows:

- An increasing reliance on paraprofessionals (often referred to as community health workers) as frontline care givers;

- The addition of preventive medicine to curative approaches;

- A noticeable shift from vertical, disease-specific global health initiatives to integrated, intersectoral programs;

- A willingness to challenge the dominant cost-effectiveness of analysis, particularly as it was used to justify a disproportionate distribution of health care resources for urban areas; and

- A heightened sensitivity to the practices of traditional healing as complementary rather than contradictory to the dominant Western medical model.17

The government working is spraying mosquito repelling smoke in a Mumbai slum to prevent malaria and other mosquito-spread diseases.

India’s Progress in Combating Malaria

In 2015, the World Health Organization set a goal of a 40 percent reduction in malaria cases and deaths by 2020 and estimated that by that deadline, malaria could be eradicated in 11 countries. The first data reports were extremely encouraging, but attrition began to set in, due to what experts feel is a lag in the billions of donor funds needed to combat the disease. The 2018 World Malaria Report health data now indicate a slowing in the elimination of the disease and even growth in disease incidents and deaths. This slide is disheartening to world health officials, particularly since early reports gave evidence of real impact against morbidity.18

India, however, according to the 2018 report, is making substantial progress: “Of the 11 highest burden countries worldwide, India is the only one to have recorded a substantial decline in malaria cases in 2017.”19

The report goes on to state that the country, which accounted for some 4 percent of global malaria cases, registered a 24 percent reduction in cases over 2016. The country’s emphasis has been to focus on the highly malarious state of Odisha. The successful efforts were attributed to a renewed government emphasis with increased domestic funding, the network of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs)—an intended 900,000 women assigned to every village with a population of at least 1,000—and strengthened technological tracking, which allowed for a focus on the right mix of control measures. The aim of India’s National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme is the eradication of malaria.20

Of the 11 highest burden countries worldwide, India is the only one to have recorded a substantial decline in malaria cases in 2017.

Remember the ever-present mosquito? Studies conducted by WHO released the findings of a major five-year evaluation reporting that people who slept under long-lasting insecticidal nets had significantly lower rates of malaria infection than those who did not use a net.21

In coordination with this national effort, GFA-supported workers distributed nets to villagers, in student hostels, among workers in the tea-growing district of Assam and many other areas while at the same time leading disease-awareness programs to tea-garden employees.

These women were happy to receive a free mosquito net for their families from GFA-supported workers.

Imagine a dusty village filled with women wearing vibrant-colored clothing. Little children dance around or stand intrigued, their huge brown eyes open. Nets are placed into outstretched hands. Women smile; gifts are always appreciated. Men listen carefully to the reasons why bed nets are essential and why it is necessary to spray the home and rooms. People bow their heads; they raise pressed hands to their faces. “Namaste,” they say giving thanks.

Envision a room at night with six to eight buzzing, dive-bombing mosquitoes and give thanks that there are organizations around the world that pass out the free gift of bed nets that not only keep humans from being stung but also prevent them from becoming wretchedly ill.

Historical Cooperation

The possibility of eradicating malaria rests in the efforts of Dr. Ronald Ross, born in Almora, India, in 1857 to Sir C.C.G. Ross, a Scotsman who became a general in the Indian Army. Reluctant to go into medicine, the son nevertheless bowed to his father’s wishes to enter the Indian Medical Service.

At first, Ross was unconvinced that mosquitoes could possibly be carriers of malaria bacteria, yet his painstaking, mostly underfunded laboratory discoveries eventually convinced him that the hypothesis of a mentor, Patrick Manson, an early proponent of the mosquito-borne malaria theory, was correct. (Manson is also considered by many to be the father of tropical medicine.) Another contemporary, the French Army doctor Alphonse Laveran, while serving at a military hospital in Algeria, had observed and identified the presence of parasitic protozoans as causative agents of infectious diseases such as malaria and African Sleeping Sickness.

From left to right: Dr. Ronald Ross, Patrick Mason, Alphonse Laveran

On August 20, 1897, in Secunderabad, Ross made his landmark discovery: the presence of the malaria parasite in humans carried by the bite of infected mosquitoes. (For obvious reasons, Ross was also the founder of World Mosquito Day.) Disease can’t be combated unless its source is identified, nor can it be optimally controlled. Certainly, without this knowledge, it can’t be eradicated. In 1902, Ronald Ross was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine.22

Here again, through the bite of the mosquito, we see the collaborative effort that undergirds progress. Three doctors intrigued with conquering the morbidity of disease take painstaking efforts to prove their theories, and each one builds on the discoveries of the other, with eventual dramatic results.

Government leaders, among others, came together during the Annual Meeting 2008 of the World Economic Forum for the “Call to Action on the Millennium Development Goals.”

Photo by World Economic Forum on Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 2.0

Change Involves Everyone

Progress is not possible without collaborative work. Statisticians, medical teams and universities, as well as local village training centers, governments of developing countries and local leadership in towns and cities must all work together. The job requires donations from wealthy donor nations as well as from national local budgets. We need the skills of technological gurus, engineers and the extraordinary capabilities of highly trained health care professionals and sociologists. In addition, we also need the involvement of those who care about the soul of humans and who have insisted, because their lives are driven and informed by a compassionate theology, that every human is made in the image of God.

GFA (SA), through its mosquito net distribution—and its many other ministries—stands central in the contemporary initiatives of health-based, community-centered, preventive health care.23

Progress is not possible without collaborative work.

These are some of the strategic players who must all be involved, and stay involved, if the MDGs, now the Millennium Sustainable Development Goals, are to be reached.

This model of interactivity, whether present-day players realize it or not, intriguingly stems from a decades-old initiative stimulated by the World Council of Churches (WCC) in the last century, based in a carefully crafted theological understanding by the Christian Medical Commission (CMC), which concurrently and cooperatively developed the meaning of health that simultaneously contributed to the WHO’s significant 1978 Declaration of Alma-Ata. This resulted in a focus on primary care as a more just and egalitarian way to distribute resources in order to treat a larger proportion of the world’s population.24

The United Nations Building in New York in 2015, displaying the UN’s development goals and the flags of the 193 countries that agreed to them.

Photo by Amaral.andre on Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 4.0

This forgotten story needs to be resurrected because it demonstrates the power of intentional intersectoral cooperation between secular and religious health outreaches. It also exemplifies a more holistic redefinition of the meaning of health that has the potential to positively impact disease-ridden environments in the many populations that are generally minimally treated or completely untreated in developing countries. In a day when Western technologically centered medicine, driven by what some in health communities are starting to call the “industrial medical complex,” is beginning to wane in its understanding of the meaning of superior patient-centered care, this model needs to be adapted to what we think of as the more sophisticated treatment approaches in health care.

Our Friends, the Critics (Because Their Criticism Makes Us Think)

Let’s first take a quick look at what critics of faith-based medical outreaches have to say. Instead of delving into the academic literature, which though informative often provides a tedious plod through footnotes and specialized terminology, let’s look at the growing field of “opinion” journalism.

Brian Palmer Photo credit nrdc.org.

After the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Liberia, Africa, an article appeared in Slate Magazine by Brian Palmer, a journalist who covers science and medicine for the online magazine. This periodical represents an admittedly liberal perspective, and that bias, though the author attempts to play fair, is shown even in the headline to his report: In Medicine We Trust: Should we worry that so many of the doctors treating Ebola in Africa are missionaries?” Great lead line; it certainly caught the attention of my friends and colleagues who work in medical missions.

Palmer summarizes his basic critique in this paragraph: “There are a few legitimate reasons to question the missionary model, starting with the troubling lack of data in missionary medicine. When I write about medical issues, I usually spend hours scouring PubMed, a research publications database from the National Institutes of Health, for data to support my story. You can’t do that with missionary work, because few organizations produce the kind of rigorous, peer-reviewed data that is required in the age of evidence-based medicine.”25

Although PubMed is a worthy venue for medical specialists as well as the generalist writing in the field—with some 5.3 million archived articles on medical and health-related topics—it alone may be a truncated resource for the kind of information that could have more richly framed this article. Interviews with at least a few boots-on-the-ground, living faith-based medical professionals who have given their lives to wrestling with the health care needs in countries far afield from Western medical resources, might also have been a better means of achieving a professional journalistic approach. In addition, there is a whole body of evidence-based research that a superficial treatment such as this did not access.

Dr. Bill and Sharon Bieber

Photo credit Healing Lives.

Sharon Bieber of Medical Ambassadors International responds to the Slate article out of a lifetime of framing health care systems with her husband, Dr. Bill Bieber, in mostly underdeveloped nations in the world. It is important to note the Canadian government awarded these “medical missionary types” the Meritorious Service Medal—an award established by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to be given to extraordinary people who make Canada proud—for their work of establishing the Calgary Urban Project Society. The Calgary Urban Project Society became the model across all Canada for helping those most in need (many of them homeless) by providing health care, education and housing—all this long before the concept of holistic treatment or an integrated approach engaging mind, body and spirit was part of the common literacy of health professionals. This, to be noted, was accomplished by the Biebers while on an extended furlough while their children finished high school—an interregnum before the two headed back to the South China Seas to fulfill their lifetime calling of working with national governments to establish primary health care systems along with improving tertiary systems in the countries where they landed.

Bieber writes, “Author Brian Palmer even queries the reliability of the mission doctors, who work in adverse and under-resourced conditions. The lack of trust seems to be justifiable, he infers, because they rarely publish their accomplishments in the ivory towers of academia! When they explain to patients they are motivated by the love of Jesus rather than financial gain, somehow that is ‘proselytizing.’ Would it be nobler, I wonder, if doctors were to tell them that the danger pay was good or that they desire adventure or fame? These are unproductive and unfounded arguments by critics who clearly have their own axes to grind, and at a time when the world crisis calls for everyone to roll up their sleeves and get to work in solving the problems facing us all.

“Surely the relief and development organizations that are out there in the world can come to the same conclusion on this one thing—everybody is needed in order to fight diseases such as Ebola, HIV/AIDS or tuberculosis; every agency has strengths that will add to the synergy of the whole. Whether faith-based, local and national government or secular NGO, all have been trained in similar techniques and scientific method. Collaboration is what is needed in order for groups that are stronger to support those that are less resourced to achieve a common goal.”26

Dr. Kent Brantly contracted Ebola while minstering in Liberia. He recovered and was featured on Time Magazine's cover, representing Ebola fighters—Time's "People of the Year." Photo credit Facing Darkness

To be fair, the Slate journalist admits to being conflicted. After listing the flaws of medical mission approaches, Palmer writes, “And yet, truth be told, these valid critiques don’t fully explain my discomfort with missionary medicine. If we had thousands of secular doctors doing exactly the same work, I would probably excuse most of these flaws. ‘They’re doing work no one else will,’ I would say. ‘You can’t expect perfection.’ ”

At least he admits to bias. Knowing my share of medical missionaries, many of whom I consider truly heroic and who are radicalizing the health care systems of the countries in which they serve for the undeniable betterment of those societies, Palmer’s approach seems a tad unprofessional as far as journalism goes. He concludes, “As an atheist, I try to make choices based on evidence and reason. So until we’re finally ready to invest heavily in secular medicine for Africa, I suggest we stand aside and let God do His work.”

"Through partnership with faith organizations and the use of health promotion and disease-prevention sciences, we can form a mighty alliance to build strong, healthy, and productive communities."

A deeper search in PubMed, driven admittedly by my own bias, led me to the excellent data-informed article utilizing research on the topic from both the scientific, theological and academic sectors by Jeff Levin, titled “Partnerships between the faith-based and medical sectors: Implications for preventive medicine and public health.”

Levin concludes with a quotation that complements his conclusion: “Former U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher, a widely revered public health leader, has made this very point: ‘Through partnership with faith organizations and the use of health promotion and disease-prevention sciences, we can form a mighty alliance to build strong, healthy, and productive communities.’ There is historical precedent for such an alliance, and informed by science and scholarship, it is in our best interest for this to continue and to flourish.”27

GFA-supported workers assisted government relief efforts after the Kerala flooding in August 2018. Here they are assembling packages of food items and other essential supplies to distribute to flood victims.

How many of us in the faith-based sector have wrestled with the theological meaning of health? What is the history of the impact of faith (particularly Christian faith because that is the bias from which I write) on the ongoing movement of medicine in these modern centuries? Why does it matter?

I recently experienced a small snapshot of current industrialized medicine. Last year I underwent a hiatal repair laparoscopic surgery. The best I can ascertain from the Medicare summary notice, which included everything administered the day of the procedure through an overnight stay in the hospital for observation with a release the next day, was the bill.

In addition, I experienced watching a son die at age 41 (Jeremy, the son who accompanied me to Mexico, leaving behind a wife and three small children, then ages 6, 4 and six months), not only from a rare lymphoma that kept him in a superior hospital in Chicago for more than five months but also from the side effects and complications of the aggressive cancer treatments. This all has given me additional perspective on medical approaches.

Bangladesh—Samaritan’s Purse treats Rohingya refugees affected by the diphtheria outbreak.

Photo credit Samaritan's Purse

No Mosquitoes in the Room Now: A Quick Look at the Impact of Faith on Modern Medical Approaches

One of the most succinct summaries of the role of faith-based activity in relationship to ongoing health needs worldwide is a paper by Matthew Bersagel Braley, “The Christian Medical Commission and the World Health Organization.” In it, the author outlines the collaborative work done between the CMC and the WHO in the 1960s and 1970s. They both, concurrently and intentionally aided by the proximity of their headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, sought to address many of the deficiencies that were (and still are) growing apace modern Western medicine with its rapidly increasing dependence upon expensive diagnostic and curative technologies.

Braley’s abstract explains, after referencing the existence of two previous international consultations organized by the World Council of Churches out of which grew the Christian Medical Commission: “What followed was a theologically informed [italics added] shift from hospital-based tertiary care in cities, many in post-colonial settings, to primary care delivery in rural as well as urban communities.”28

They saw the mandate of the church as being that of working to restore (as much as is possible) the world to God's original design.

The early consultations, Tübingen I (in Germany) and Tübingen II, had developed a theology of health that eventually culminated in a mutual understanding. Looking as they were through the lens of health and defining health as the kind of flourishing that God intended for His human creation, they saw the mandate of the church as being that of working to restore (as much as is possible) the world to that original design. Wholeness then is a kind of health—an “at oneness” with God, with fellow humans, with our communities and with our environment. As believers work toward this goal, despite the fact it will never be ultimately achieved until Christ returns, they consequently become healers or health-bringers with an emphasis on flourishing.

Health was also redefined as the ideal that God desired for the people of the earth, one that will probably not be achieved completely, but will have periodic breakouts in time. Health was seen not simply as the “absence of disease” as defined traditionally by the medical establishment, but the presence of ecological health, harmony within the community, at oneness within the individual and in his or her relationships. It was a presence of peace and a lack of warfare; it was an insistence and concern that the neglected, the poor and the oppressed should even be given preferential treatment because of the systemic unfairness, lack of parity and often true evil exercised by the powerful over the powerless.

David and Karen Mains, 1983 at Mount Hermon Conference Center, CA

Personal Reflections

These theological comprehensions and conclusions have personal meaning to me, because I’ve seen firsthand the importance of working together to help others achieve this all-encompassing health. In 1967 we planted a church on the near west side of Chicago, across the expressway from what is now the Illinois Medical District. At that time, we knew it was one of the largest medical centers in the world; now it consists of 560 acres of medical research facilities, labs and a biotechnology business incubator, four major hospitals, two medical universities and more than 450 health care-related facilities. Needless to say, our small but rapidly growing congregation consisted of many medical grad students, nurses and doctors, and social workers.

There must have been something in the international waters, because totally unaware of the groundbreaking conversations going on among the professionals concerned with health impacts on the other side of the world, David Mains, my husband and the founding pastor of our church, discovered Christ’s major preaching theme was the Kingdom of God. Salvation, or being saved, was entry level to an understanding of that preeminent theme. If the predominance of this message was correct, then it totally shifted our thinking from an individualistic interpretation of faith lived out among private lives to a corporate identity framed through the mutual understanding of Scripture’s teaching of this breakthrough concept. Our salvation was worked out in dialogue around Scriptures and in community with other spiritual pilgrims.

"How important it is when members of faith-based consultations ... across the world put aside their differences and ... design outcomes that have the possibility to alter ... whole nations for the good.

There were places in the world, I discovered as I traveled in the role of journalist, where the people used the word “I” but really meant “we.” I began to understand the Epistles often addressed readers with the word “you.” This was not an individual personal pronoun; in most cases, it was a plural pronoun requiring group action, as in “you, the people of God.” David preached a sermon series titled The Christian, the Church and Society including Christ’s two-part summary message, “Unless you are converted and become like little children, you will by no means enter the kingdom of heaven.”29 The dialogue of those Christians, listening to David’s sermon in that place and that time in history, when a whole revolutionary resistance movement was rising in our culture—against the war in Vietnam and against injustice, racism, sexism and government corruption—forced upon us a theological conversation that just didn’t happen in other places.

In addition, David, in his 30s, became the head of the Greater Chicago Ministerial Association, and we learned to dialogue across the whole body of faith-based confessions. So, we understand how important it is when members of faith-based consultations here at home or far away across the world put aside their differences and in respect and with deep listening capabilities design outcomes that have the possibility to alter cultures and societies and whole nations for the good.

A part of Samaritan’s Purse relief efforts, these men and women helped fight the Ebola pandemic that swept across West Africa in the spring of 2014.

Photo credit Samaritan's Purse

Conclusion: Our Part in World-Changing

Matthew Braley’s chapter, taken from the book Religion as a Social Determinant of Public Health, is filled with theological terminology such as epistemology and eschatology, but for the average layperson, what is most important is the Christian Medical Commission’s (CMC) understanding that God’s desire for humankind was that humans flourish in environments most optimal to health as defined not by the absence of disease but by a growing wholeness, and that the thrust of Christ’s ministry and preaching demonstrated the ways to achieve this, aptly summarized in His explanation that we are to love God and love our neighbor as ourselves. The CMC’s struggle to understand redemption as a growing wholeness eventually resulted in the “game-changing” 1978 Declaration of Alma-Ata, the conference out of which the Millennium Development Goals proceeded.

Everybody

is needed in order to fight diseases such as Ebola, HIV/AIDS or tuberculosis

All eight of those goals, delineated earlier in this article, are undergirded by and initiated from a theological understanding of the health emphasis, the redemptive purpose, the salvific meaning demonstrated by Christ and often emulated (though not often enough) by His followers. The MDGs are basically communal in the fact that they bring healing in the large sense of being at peace—or at home—with one’s self; with one’s family, friends and community; and with one’s place in the world. And they cannot be accomplished in a village or a nation or globally without the commensurate communal action of as many entities as possible, giving whatever they can to eradicate whatever suffering can be done away with through these human initiatives.

The participants at Tübingen I and II, the emergent Christian Medical Commission, and thousands of others of us who have, as the Jewish phrase states, worked at “repairing the world” for most of our lives would insist this is God’s work, in God’s way and with God’s help. Fortunately, as Bishop Tutu of South Africa said when he addressed the 2008 61st-annual meeting of the World Health Assembly, the World Health Organization’s governing body, “It is a godly coincidence … together WHO and WCC share a common mission to the world, protecting and restoring body, mind, and spirit.”30

As Sharon Bieber responded: “Surely the relief and development organizations that are out there in the world can come to the same conclusion on this one thing—everybody is needed in order to fight diseases such as Ebola, HIV/AIDS or tuberculosis; every agency has strengths that will add to the synergy of the whole.”

So when we see groups like GFA (SA) working to hand out hundreds of thousands of mosquito nets to fight malarial infection, when we know tens of thousands of wells have been dug to provide clean water, and when we understand that the effectiveness of the message of Christ can often be measured by how many latrines have been built in a village or a city, we understand that this is what is necessary to help the participants in our world discover true, full health.

This family received a mosquito net at a GFA-supported Christmas gift distribution. Now they have protection from mosquitos while they sleep.

Who knows what consultations among desperate folk with common passions are forming even now that will salvage our world at some future critical juncture?

Perhaps you would like to be part of that network of people determined to spread goodness (God-ness) throughout the world. First, begin by educating yourself. Read the book Half the Sky by Nicholas Kristof and his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, which includes a compendium of organizations seeking volunteers. The authors do not hide how impressed they are with conservative faith-based organizations doing work in the world. Another book to read is To Repair the World by Paul Farmer, a medical doctor many consider to be a modern-day hero.

“This is a bold read by a humble visionary. For those who care about humanity, this is a handbook for the heart,” reads a blurb on the back cover written by Byron Pitts, the chief national correspondent for CBS Evening News.

Then circle one of the volunteer efforts that seems to be calling your name. Become an activist. No need to travel overseas (although that is highly recommended). There is plenty of work to do at home, wherever home may be for you. Just don’t only think about doing something: Do it! (I’m going to look up volunteering for disaster-relief training with The Salvation Army—or the American Red Cross—and I’m 76 years of age!)

At the end of the parable of the Good Samaritan, Jesus says to the young lawyer, “Go and do likewise.” No, there’s no danger pay for the faith-based health worker. I don’t know of any who have become wealthy. Most of them belong to the league of the nameless. For these, fame is not a motivator either; it generally gets in the way of doing the job.

But mercy? Compassion? Daring to go where others dare not go? Becoming more and more like Jesus? Yep, these are where most of those I know find deep satisfaction. A remarkable man once said, “Go and do likewise.” And they do.

Is that a mosquito I hear buzzing above my ear?

It only takes one mosquito bite to raise a welt.

It only takes one mosquito to kill a child.

It will take a multitude of innovators (believers or nonbelievers) to fight for the Kingdom to “come on earth as it is in heaven.”