Increasing demand on rivers, lakes and streams, compounded by changing weather patterns, population growth and economic development, is leaving us in a world where many people are struggling to find enough fresh water to survive. (I'll develop this topic below, to add to our previous essays on water stress globally, solutions to the world water crisis, and those that are dying of thirst.)

Nepal: As the water levels underground started shrinking, people in this remote Nepali village had to resort to collecting water from small puddles in the forest for drinking. This boy was asked by his parents, who were working in the field, to fetch water from one of these puddles, but the water from these open areas is often full of germs and bacteria as animals also use them.

Water is a resource that is becoming more precious than gold, according to various headlines from around the world.8182 One news story included a somber prediction by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that future climate instability will create serious water shortages.83

In the IPCC August 2020 report, the Geneva-based organization forecast that rising temperatures over the next two decades will spark changes in the world’s water cycle, with wet areas becoming wetter and arid lands prone to greater drought.84

“There is already strong evidence that we are seeing such changes,” said Professor Mike Meredith, a lead author for IPCC and scientist at the British Antarctic Survey. “In some dry regions, droughts will become worse and long lasting. Such risks are compounded by knock-on consequences, such as greater risk of wildfires, [which] we are already seeing.”85

Just after the report’s release, the Cable News Network (CNN) reported that Middle Eastern countries like Iran, Iraq and Jordan are pumping vast amounts of water from the ground for irrigation to improve food self-sufficiency. Charles Iceland, global director of water at the World Resources Institute, told the network that while this can compensate for a decrease in rainfall, it also results in falling groundwater levels.86

The four-person CNN team report noted areas around the globe where that’s happening, like in Iran, where a vast network of dams sustains an agricultural sector that drinks up about 90% of the water the country uses. “Both declining rainfall and increasing demand in these countries are causing many rivers, lakes, and wetlands to dry up,” Iceland told CNN. “The consequences of water becoming scarcer are dire: Areas could become uninhabitable; tensions over how to share and manage water resources like rivers and lakes could worsen; more political violence could erupt.”87

Western US: In the 1980s the waters of Lake Mead flowed rapidly over the Hoover Dam spillway, but after many years of drought along the Colorado River, the water level has dropped dramatically. Photo by LasVegasNevada.gov

The situation threatens wealthier countries, too. The New York Times reported larger future cuts in water consumption are likely for 40 million people in the West who rely on rivers. For the first time ever, last August, the U.S. federal government declared a water shortage at Nevada’s Lake Mead, a main reservoir for the Colorado River. Initially, that will mostly affect farmers in Arizona. In addition to seven U.S. states, two in Mexico draw water from the Colorado. Besides providing drinking water, it irrigates desert crops and generates hydroelectric power. Scientists say the only way to alleviate the problem is to reduce demand.88

“As this inexorable-seeming decline in the supply continues, the shortages that we’re beginning to see implemented are only going to increase,” said Jennifer Pitt, who directs the Colorado River program at the National Audubon Society. “Once we’re on that train, it’s not clear where it stops.”89

Water is a resource that is becoming more precious than gold, oil or gas, according to various headlines from around the world. But the consequences of water becoming scarcer are dire — as areas become uninhabitable, tensions worsen and violence could erupt.

Weeks before this news, analysts at the London-based financial giant Barclays issued a research note that identified water scarcity as the most important environmental concern for global consumer staples, affecting everything from food and beverages to agriculture and tobacco.90 Circle of Blue reported that major companies are increasingly concerned about water’s availability, with the average price between 2010 and 2019 increasing by 60 percent in the 30 largest U.S. cities.91

Beth Burks, director of sustainable finance at S&P Global Ratings, told CNBC, “Water scarcity is really important because when it runs out you have really serious problems.”92

India: During the months of April and May this area in Maharashtra and the villages around it face drought and a severe shortage of fresh water. The rivers, canals, and wells completely dry up, causing great difficulties for people and their animals.

Fresh Water Scarcity - the "Invisible" Hand Behind Many Global Crises

Water problems especially affect the 1.1 billion people who lack access to a basic drinking source.93 Then there are millions more who devote many waking hours to obtaining it. According to the non-governmental organization H2O for Life, women and children in many communities spend up to 60% of each day collecting water.

In Africa, more than

25% of the population

spends more than 30 minutes (sometimes up to six hours) walking nearly four miles to get enough water for the day.94

A 2021 report for the Council on Foreign Relations identified the Middle East and North Africa as the worst for physical water stress. In addition to receiving less rainfall, the countries’ fast-growing, densely-populated urban centers require more water. It’s estimated that 70% of the world’s fresh water is used for agriculture, with another 19% going to industrial use and 11% for domestic, including drinking.96

Assam: Before a Jesus Well was installed in her village, this 30 year old mother of four had to make the fifteen minute walk from her home to the closest water source. She would fetch water four-five times in a day, carrying the heavy load on her head. This water was contaminated though, and the family would suffer from skin diseases and other health issues like diarrhea, typhoid, stomach problems, etc.

Water problems directly affect 1.1 billion people who lack access to a basic drinking source. Then there are millions more who have to spend up to 60% of each day collecting water.

The report for the CFR said water scarcity is usually divided into two categories: 1) Physical scarcity related to ecological conditions and 2) Economic scarcity because of inadequate infrastructure.97

“The two frequently come together to cause water stress,” wrote Claire Felter and Kali Robinson in their report entitled: “Water Stress: A Global Problem That’s Getting Worse.” “For instance, a stressed area can have both a shortage of rainfall as well as a lack of adequate water and sanitation facilities. Experts say that when there are significant natural causes for a region’s water stress, human factors are often central to the problem.”98

Shaz Memon (centre), founder of Wells on Wheels. Photo by Wells on Wheels

Water scarcity is the “invisible” hand behind many humanitarian crises, said Shaz Memon, a British entrepreneur and founder of the charity Wells on Wheels. In a recent commentary, he named Yemen as one of the world’s most water-scarce countries, a condition leading to social and political upheaval. For example, he notes that in Nigeria the Boko Haram insurgency in 2010 arose because of a demand for clean drinking water. Drought and water scarcity was also a pivotal factor behind Syria’s civil war as well, according to Memon.

“Water is a precious, life-giving commodity; it becomes more scarce because it isn’t treated as such,” Memon wrote. “Unlike gold, oil or gas, it is not priced in relation to its global scarcity. … However, there are some who understand water’s status as a valuable commodity. Goldman Sachs has said water could be the ‘petroleum of the 21st century.’”99

Such observations underscore the significance of the United Nations’ World Water Day, set for March 22 with the theme ‟Groundwater: Making the Invisible Visible.” The UN calls groundwater a vital resource that provides almost half of all drinking water worldwide, sustains ecosystems, maintains the baseflow of rivers, and prevents land subsidence and seawater intrusion.100

These women in Assam have to visit the river several times daily to fetch water that is dirty, muddy and becoming increasingly scarce.

In the hot summer days, when other water sources dry up, this pipe bringing water down from a fountain in the hills is the only source of water this village in Nepal has.

New Technologies Promise Relief

Despite an often bleak scenario, there are optimistic signs that technology can help address shortages. A recent story discussed how Watergen, an Israeli-based company uses air-to-water technology to deliver drinking water to remote areas. Its machines filter water vapor out of the air, the largest of which can provide 6,000 liters a day and has been used at hospitals in the Gaza Strip and rural villages in central Africa.101

Watergen’s president, Michael Mirilashvili, told the BBC that its system alleviates the need to build water transportation systems, dispelling worries about heavy metals in pipes, cleaning contaminated groundwater, or polluting the planet with plastic bottles.102

“A study conducted by scientists from Israel’s Tel Aviv University found that even in urban areas … it is possible to extract drinking water to a standard set by the World Health Organization,” wrote business reporter Natalie Lisbona. “In other words, clean water can be converted from air that is dirty or polluted.”103

Despite its increasing scarcity, there are optimistic signs that technology of various kinds can help address fresh water shortages around the globe.

Watergen’s isn’t the only such technology being developed. A story by science journalist Duane Chavez outlined two others.

The first is a system proposed by engineers from the State University of New York at Buffalo and the University of Wisconsin. It uses carbon paper evaporators and condensers that emit more energy than they absorb, reducing the temperature below the dew point to achieve vapor condensation.

The other is a passive system developed by researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California at Berkeley. It extracts water from dry air by consuming solar energy, based on a new type of porous material called Metal-Organic Frameworks.104

Other methods to address freshwater scarcity include the following:

Scientists from the UK’s University of Manchester are working on a desalination alternative—a graphite oxide sieve that retains salt and only allows water to pass through. In 2019, the university’s National Graphene Institute began collaborating with a portable water filtration company to develop new water purification devices based on this technology.107

LifeStraw is a plastic tube nearly nine inches long and about an inch wide that has a filtration system to remove protozoa, bacteria and other harmful materials from water. One unit can provide personal water filtration for up to three years. The technology is marketed in bottle format as well as in larger systems and has been used in places like Haiti, Rwanda and Pakistan.105

A “Safe Water Book” developed by a chemist and her husband contains tear-out pages that are water filters and can provide germ-free water for four years. Their company, Folia Water, has tested the product in Africa, Asia and Latin America and begun distribution in Bangladesh. A similar product, “The Drinkable Book,” has been developed by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University.106

Associate Professor Haolan Xu leads a team of researchers at the University of South Australia who have developed a device to help with water purification. Photo by University of South Australia

Meanwhile, researchers at the University of South Australia have refined a technique to derive fresh water from sea water, brackish water or contaminated water through solar evaporation. The device includes a photothermal structure that sits on the surface of a water source and converts sunlight to heat, rapidly evaporating the uppermost portion of the liquid.108

“We have developed a technique that not only prevents any loss of solar energy, but actually draws additional energy from the bulk water and surrounding environment,” said Haolan Xu, the associate professor who leads the team. “[That means] the system operates at 100 percent efficiency for the solar input and draws up to another 170 percent energy from the water and environment.”109

Assam: The only water available in this rural village has a very bad odor and taste. If stored in a container, the color of the water changes and a layer of chemicals can be seen. The water has all been contaminated by arsenic, but is being ingested by the entire community.

Conservation Efforts are Helping

Cape Town, Africa: After a alarming water shortage in 2018, conservation efforts have brought stability to Cape Town's ongoing water supply.

Sometimes the solutions aren’t as dazzling but still matter, as demonstrated in San Antonio. The southern Texas city found itself in a legal battle 31 years ago over arguments it pumped too much water from the Edwards Aquifer, a major groundwater source. The Sierra Club’s victory in the case forced San Antonio to limit withdrawals.110

Conservation efforts that followed included better irrigation and landscaping, installation of water flow sensors, and rebates to residents who install pool filters or convert grass into patios. Despite 80% growth in their population since 1991, San Antonio has decreased per-person water use by 20%.111

Cape Town, South Africa, also had to reduce water consumption after nearly running dry in 2018. Three years later, “I definitely think that there has been a permanent behavior shift,” said Limberg, a local appointed official and a mayoral committee member for waste and water in Cape Town . “There’s definitely been a greater awareness to conserve water, and of how incredibly finite this resource is, and how vulnerable we are if we face a shortage of water.”112

Enhanced water meters also help. WaterOn, a device produced by India-based Smarter Homes, is a metering and leakage prevention system. In 2019 it saved 40,000 apartment households an average of 35 percent of their water consumption. In one region it saves millions of gallons of water each month.113

Low-tech Tools Can Also Be Economical Solutions

Then there are more basic solutions that help numerous people, like drilling wells in areas that lack access to fresh water. This video below shares the story of one village in Nepal that benefitted from this approach provided by their local church.

Nepal: Getting fresh water was a constant time-consuming challenge for this entire village until the local church installed a Jesus Well which resolved the water shortage and benefitted their entire community.

For just over two decades, GFA World has helped drill Jesus Wells in Asia. These wells provide clean water at a cost of less than five dollars per person.114 GFA also distributes BioSand water filters, devices that use concrete, different types of sand and gravel to remove impurities, providing water for drinking and cooking that is 98 percent pure.115

The value such low-tech solutions provide is evident in the numbers: it costs about $1,400 to drill a Jesus Well, which may provide clean water for up to 300 people per day for 10 to 20 years. While a BioSand water filter only supplies water to one family at a cost of $30 per unit, it offers a readily available clean drinking source for a similar five-dollar figure.

Over the years, more than 38 million people in Asia have received safe drinking water through GFA World’s clean water initiatives. In addition to providing water wells and filters, GFA World conducts free medical camps that offer treatment for such water-linked ailments as diarrhea—the most serious illness children face worldwide.

This Jesus Well in Assam has become very useful to the villagers who did not have clean drinking water, especially during rainy season. They now use the water for drinking, cooking, washing clothes, bathing, and even water their cattle with it.

Despite complexities resulting from pandemic restrictions, the faith-based organization continues to meet a desperate need, with founder K.P. Yohannan noting that in the next 20 years, global water demand is expected to surge more than 50%.

Dr. K.P. Yohannan,

GFA Founder

“This desperate situation is especially acute in Asia, where millions of families get their drinking water from the only source available to them—often a dirty river or stagnant pond, which are breeding grounds for parasites and deadly bacteria,” Yohannan said. “It’s a problem we as a ministry have been actively helping to combat for years.”

This ends the updates to our three previous Special Reports,

which are featured in their entirety below.

Water Stress:

The Unspoken Global Crisis Nations worldwide, both rich and poor,

are struggling for safe drinking water.

Water problems are often big news, whether it’s ongoing crises in American locales like Flint, Michigan or Newark, New Jersey; in 11 cities across the world forecasting as most likely to run out of drinking water; or the widespread concern that two-thirds of the world will face shortages by 2025.

Andrew Steer, President and CEO of the World Resources Institute

Photo by World Resources Institute

And yet, “water stress is the biggest crisis no one is talking about,” says Andrew Steer, President and CEO of the World Resources Institute. “Its consequences are in plain sight in the form of food insecurity, conflict and migration, and financial instability.”59

One recent report from World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF) says that 785 million people lack a basic drinking-water service. Globally, at least 2 billion people use a source contaminated with feces. Contaminated water can transmit diseases such as diarrhea, cholera, and dysentery.60 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control says an estimated 801,000 children younger than 5 perish from diarrhea annually, mostly in developing countries.61

Not only is safe, readily available water important for public health, WHO says improved water supply, sanitation, and better management of resources “can boost countries’ economic growth and can contribute greatly to poverty reduction.”62

Still, nearly 50 years after the U.S. adopted the Clean Water Act (regulating surface water quality standards and discharge of pollutants into water) and close to 30 years after the United Nations started observing World Water Day (Mar. 22), getting clean water to everyone remains a monumental challenge.

That’s true even in developed nations. More than 2 million Americans lack access to running water and indoor plumbing; another 30 million live in areas lacking access to safe drinking water.63 Last September, an investigation into a 6-year-old boy’s death led to detection of a brain-eating amoeba in the water supply of Lake Jackson, Texas, an hour south of Houston.64

But it isn’t just the U.S. struggling to provide an adequate supply. Two years ago, BBC News chronicled 11 cities most likely to run out of drinking water. Topping the list was Cape Town, South Africa, which the BBC said was “in the unenviable situation of being the first major city in the modern era to face the threat of running out of drinking water.”65

Cape Town has thus far avoided that fate by instituting usage restrictions, but that city and 10 others continue to face a water shortage:

40% of the population

in Sao Paulo, Brazil’s financial capital, faces extremely high water stress.

20 million inhabitants

in Beijing, China, have just 15 percent of the fresh water they need.

97% of Egypt's water

in Cairo, the Nile River, is increasingly polluted.

20% of the population

in Mexico City, only get water from their taps a few hours a week.

Pushing close to capacity

the water usage in London.

Interestingly, only Mexico is listed by WHO and UNICEF among 10 countries with the worst drinking water. The other nine include Congo, Pakistan, Bhutan, Ghana, Nepal, Cambodia, Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Uganda. Tales of woe in the report include 40 percent of Ugandans having to travel more than 30 minutes for safe drinking water.

Only One-third

of Bhutan’s drinking water is safe from contamination

15% of Nigerians

drinking from unimproved sources, even though it is one of the fastest-improving nations for water quality.66

In two previous special reports for GFA (SA) entitled “Dying of Thirst: The Global Water Crisis,” and “Solving the World Water Crisis ... for Good,” we unpacked the global quest for access to safe, clean water, and how lasting solutions can defeat this age-old problem. This article highlights continuing water stress problems worldwide, and various solutions that are emerging to deal with a crisis issue that is too often underdiscussed.

Pandemic Problems to Make Global Water Crisis Worse

As if the situation wasn’t bad enough, the pandemic of 2020 exacerbated conditions. In a forecast just prior to last year’s World Water Day, the UN said, “A continuing shortfall in water infrastructure investments from national governments and the private sector has left billions exposed to the COVID-19 pandemic.”67

Ensuing developments justified the warning. Soon after, grocery stores in central California took to rationing bottled water to deal with the pandemic’s effects that posed serious health risks for residents in rural farmworker communities, where tap water is often fouled by agricultural pollution.68

Water stress presents formidable challenges to many people in Asia and Africa, like this young boy in Africa, needing to take a drink from this mirky pond.

Photo by Frederick Dharshie, CIWEM, Environmental Photographer of the Year Gallery

In long-plagued Flint last summer, 55-year-old Cynthia Shepherd told The Detroit News that, coupled with the extended water crisis there, the pandemic was making it “tough.” “I’ve known a few people who have died, and it’s scary,” says Shepherd.69

Soon after reopening for the 2020-21 school year, school officials in five Ohio towns announced they had found legionella—the bacteria that can cause a serious type of pneumonia called Legionnaires’ disease—in their water supplies. So did four districts in Pennsylvania. Ironically, precautions taken to prevent infection risks could have added to the problem.

“Stagnant water in unused drinking fountains or sink plumbing could be a good reservoir in which the bacteria could grow,” wrote New York Times reporter Max Horberry. “And shower heads like those found in locker rooms are common places for Legionella to proliferate.”70

But it’s worse elsewhere. Countries in Africa and South Asia, where 85 percent of the world’s people live, face formidable challenges. One report said during the outbreak a lack of clean drinking water and hygiene practices became a major concern for cities in the developing world, especially in slums, urban fringes, and refugee camps. Since COVID-19 has focused global attention on the need for frequent handwashing, drinking water and personal hygiene, The Conversation said political leaders will have to give attention to quality as well as access.

“It will be an even more daunting task, in both developed and developing countries, to regain the trust of their people that water they are receiving is safe to drink and for personal hygiene because of extensive past mismanagement in most areas of the world,” the publication observed.71

African child drinking polluted dirty water from a pond in his neighborhood.

Photo by Mzilikazi wa Afrika

In an article for GeoJournal, Professor Albert Boretti noted that technological improvements that helped deal with increased demand for water, food, and energy since 1950 were not enough to avoid a water crisis. Not only have worldwide coronavirus cases (as of Aug. 4, 2020) surpassed 18.4 million and fatalities reached almost 700,000, containment measures aimed at limiting infections damaged the world economy, he said.

“This will limit social expenditures in general, and the expenditures for the water issue in particular,” Boretti said. “The water crisis will consequently become worse in the next months, with consequences still difficult to predict. This will be true especially for Africa, where the main problem has always been poverty. ... More poverty will translate in a lack of food and water, potentially much more worrying than the virus spreading.”72

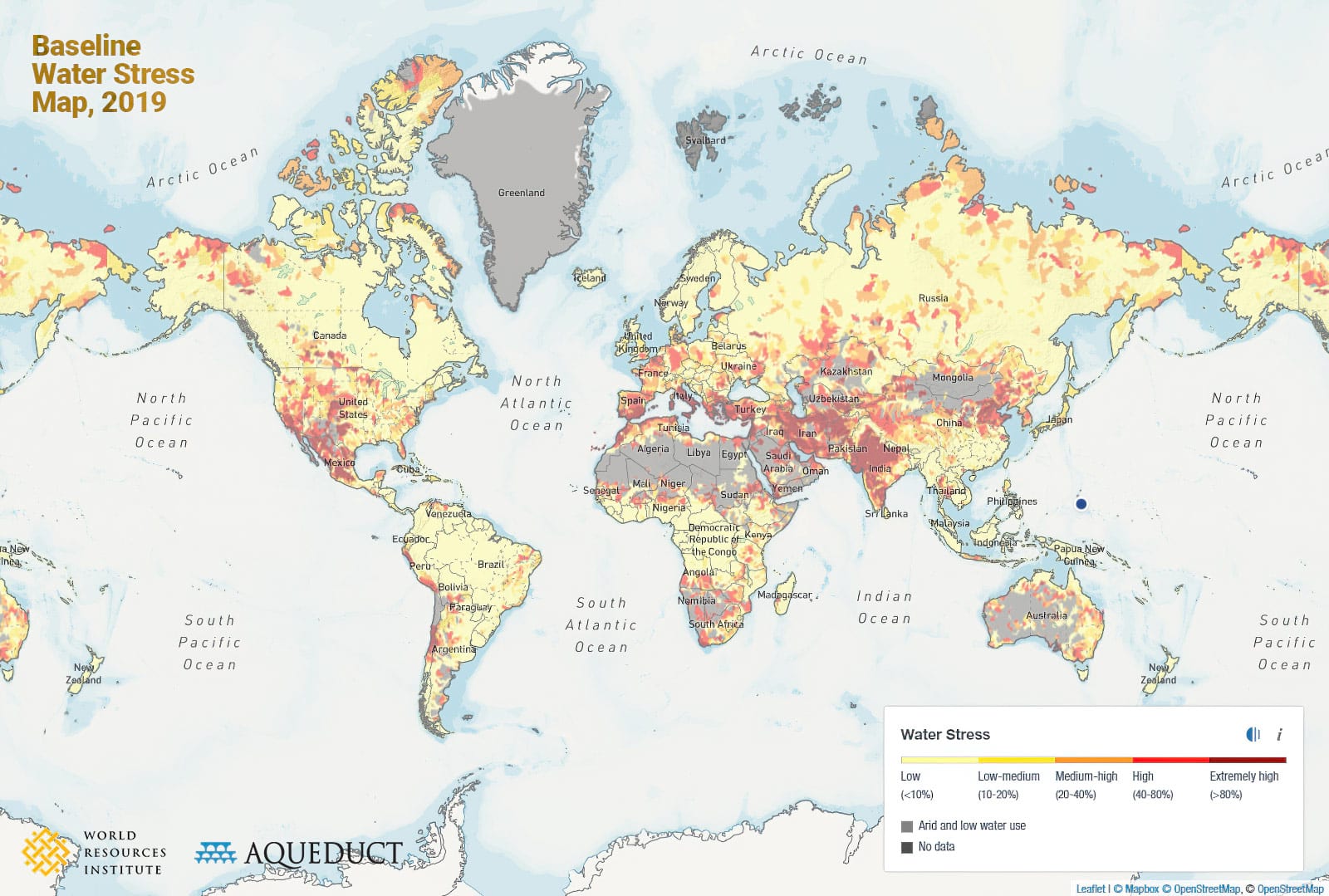

Baseline water stress measures the ratio of total water withdrawals to available renewable surface and groundwater supplies. Higher values indicate more competition among users. Photo credit: World Resources Institute, Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas (CC BY 4.0) • Data Source: WRI Aqueduct 2019

Singapore Water Crisis Solutions

When it comes to cleaning up water, the Asian city-state of Singapore is a success story. For more than a century after the British settled there in 1819, the Singapore River was the focus of global and regional trade. That also brought pollution associated with commercial activity, such as industries, squatter colonies and food vendors dumping garbage, sewage, and industrial waste into the river.

Aerial view of the clean Singapore river near Clark Quay in the central area of Singapore. Photo by Amos Lee

For more than a century, various commissions proposed alternatives for improving navigation and solving pollution, including a 1950s report suggesting improvements costing $30 million. For various reasons, it was never implemented, say the authors of an academic paper on the history of the clean-up.73

However, in the 1960s, the prime minister set in motion a plan that included a call for water and drainage engineers in two departments to work together to resolve environmental problems. Polluters were told to move, families relocated to high-rise public housing, and a series of other steps were taken that cost $300 million.

“When the costs of the rivers cleaning programme are compared with the benefits, it is clear that it was an excellent investment,” said lead author Cecilia Tortajada. “The river cleaning programme had numerous direct and indirect benefits, since it unleashed many development- related activities which transformed the face of Singapore and enhanced its image as a model city in terms of urban planning and development. Most important, however, was that the population achieved better quality of life.”74

These women in Asia typically have to walk for hours in search of water sources that are often just filthy ponds or dirty lakes, and typically contaminated with waterborne illnesses. As they are without options, they do this knowing the water could bring sickness or death to their families.

Other Global Water Crisis Solutions

Cleaning up water is only part of the solution to the global water crisis. The main part will be finding additional water sources, which is where advancements in desalination (also known as desalinization) offer encouragement. According to one report, desalination capacity is expected to double between 2016 and 2030.75

One Columbia University team achieved a zero-liquid discharge without boiling the water off—a major advance in modern desalination technology. Photo by Chenyu Guan

Last June, Columbia University announced engineering researchers have been refining desalination through a process known as temperature swing solvent extraction (TSSE). The school says TSSE is radically different from conventional methods because it does not use membranes to refine water. In a paper for Environmental Science & Technology, the team reported their method enabled them to attain energy-efficient, zero-liquid discharge (ZLD) of these brines.76

“Zero-liquid discharge is the last frontier of desalination,” said Ngai Yin Yip, an assistant professor of earth and environmental engineering who led the study. While evaporating and condensing the water is the current practice for ZLD, it’s very energy intensive and prohibitively costly. The Columbia University team was able to achieve ZLD without boiling the water off—a major advance in desalination technology.77

Among other advances is work by a research group at Spain’s University of Alicante, which has developed a stand-alone system for desalination that is powered by solar energy. A second solar-powered system developed by researchers in China and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was announced in February 2020.

Without clean water, youngsters worldwide are susceptible to many waterborne diseases, which prevent them from attending school and can thereby keep them trapped in a persistent cycle of poverty.

There is also commercial potential, as shown by 11 plants operating in California, with 10 more proposed. One in suburban San Diego turns 100 million gallons of seawater into 50 million gallons of fresh water daily, which it pipes to various municipalities. While it costs twice as much as other sources, the water resources manager for the San Diego County Water Authority says it’s worth it.

“Drought is a recurring condition here in California,” said Jeremy Crutchfield, Water Resources Manager at the San Diego County Water Authority. “We just came out of a five-year drought in 2017. The plant has reduced our reliance on imported supplies, which is challenging at times here in California. So it’s a component for reliability.”78

This mother and child are both enjoying a refreshing splash of the clean drinking water provided through a Jesus Well. Before these wells were built, women and children from the village walked miles back and forth to fetch water, which was most often contaminated. Now their villages enjoy the relief and love that these Jesus Well brings. The fresh, clean water is available to the villagers year-round, right in the middle of town, saving them time, and concerns about waterborne diseases.

Micro Solutions to the Global Water Crisis

3.4 million people die every year from waterborne diseases caused by contaminated, dirty water. A simple BioSand water filter can change that, providing water that is 98% pure after filtration.

For every macro problem there are also micro solutions. In addition to the United Nations, there are numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and charities fighting for clean water, like water.org, the nonprofit founded by actor Matt Damon and Gary White. Faith-based World Vision is one of the largest NGOs and provides clean water in addition to its child sponsorship and disaster relief work.

Another active NGO is GFA (SA) (GFA), which initiated water well drilling projects in 2000 after the Lord put a burden on a donor’s heart about the need for clean water. He contacted the ministry to ask if it would allow wells to be built in needy communities served by GFA pastors—and sponsored the first 10, known as Jesus Wells. Drilled 300 feet (91 meters) or deeper into the earth, these wells often provide clean water for 300 or more people per day.

Over two decades, the results have been phenomenal. GFA has drilled a cumulative total of more than 30,000 wells and today is completing around 4,000 each year throughout Asia.79 In addition to helping entire villages, Gospel for Asia (GFA) provides solutions for individuals and families through BioSand water filters, designed for home use. Capable of removing 98 percent of biological impurities, the filters can last for up to 20 years with proper care. By the fall of 2020, the ministry had distributed more than 58,000 filters.

BioSand water filters are bringing joy to families in South Asia! Many people in this area have to drink dirty water out of stagnant ponds, for lack of access to clean water sources, so after receiving a water filter like this one, their family can now drink clean, tasty water instead.

The blessings such help provides can be seen through a number of individual stories. In one of the first villages where a Jesus Well was installed, residents used to drink from a pond also used for bathing, irrigation, and cooking. Summer droughts often evaporated the dirty pond water; a well near the village went from providing clean water to a brownish substance in a matter of months and was later abandoned.

Now, the clean well has become part of the community’s fabric. Says a Gospel for Asia (GFA) pastor whose church is next to the well: “I feel very happy to know that this is one of the first Jesus Wells. It’s not easy to have a well maintained for this many years; because anybody can install a well, but maintaining it for almost [20] years, where it still gives clean and good drinking water, it is not easy. That makes me very proud and happy.”80

Founder of Gospel for Asia (GFA), K.P. Yohannan, says the faith-based NGO is helping thousands of needy families, especially children. Without clean water, he says youngsters are susceptible to many diseases, which prevent them from attending school and can thereby keep them trapped in a cycle of poverty.

Dr. K.P. Yohannan,

GFA Founder

“We attack the water crisis globally by installation of wells in a village or BioSand filters in homes,” Yohannan says. “We did a study in our medical camps and found the No. 1 issue for children in South Asia was either diarrhea or upper respiratory infections. Our ultimate goal to give kids an education so they can get a better job is compromised if they’re sick.”

Waterborne diseases causing stress, sickness, and even death can be addressed and resolved with proper solutions, like BioSand water filters and fresh-water wells.

BioSand Water Filters

If you’d like to make a personal impact on the world water crisis, consider giving a needy family a simple BioSand water filter. For only $30, GFA World can manufacture and distribute one of these effective filters to a water-compromised family in Asia or Africa and provide them with clean, safe water for years to come.

Jesus Wells

Or, consider giving toward the $1,400 average cost to install a Jesus Well for an entire community. Jesus Wells can serve 300 or more people with safe, clean drinking water for 10-20 years.

Either solution is a simple and effective way to take part in helping reduce water stress in this world and provide micro solutions to the global water crisis for people in need of clean, safe drinking water.

This ends the updates to our two previous Special Reports,

which are featured in their entirety below.

Solving the World

Water Crisis … for GoodLasting Solutions Can Defeat an Age-old Problem

For millions of people around the world, finding clean water is a daily struggle. Like all of us, they need water to drink, to wash in and to grow their crops. When they can’t find it, terrible things happen: Farmers lose their livelihoods; people suffer the slow, insidious effects of chronic dehydration; entire families contract dysentery or arsenic poisoning; and too often, people die.

The issue is really twofold: 1) In many places, there simply isn’t enough water available; and 2) Often, the water that people do have is contaminated. Remedies exist for both problems, ranging from complex and costly to astonishingly simple. But sadly, most of the people who desperately need these solutions don’t have access to them—yet.

In my previous special report for GFA (SA) entitled “Dying of Thirst: The Global Water Crisis,” I unpacked the global quest for access to safe, clean water. This article highlights three major initiatives that are addressing the world water crisis and one practical way you can personally get involved.

Globally, women and girls spend 200 million hours a day collecting water.1 This would be the equivalent to building 28 Empire State Buildings every single day!2

Wells Find Water Where There Is None

Roughly 40 percent of the world’s land mass is arid or semi-arid, receiving little rainfall. About 2 billion people live in these dry areas,1 90 percent of them in developing countries2 where water infrastructure is limited or nonexistent. Yet they all need water to survive. How do they find it?

This drilling rig is used to create a Jesus Well. Machines like this one will drill bore wells more than 600 feet deep, allowing up to 300 families a day to draw good, clean water even in the driest seasons.

For many of them, each day begins with a trek to the nearest waterhole, which may be miles away. Life becomes a dreary quest for survival as they spend precious hours seeking the day’s supply of water. That leaves little time or energy for more productive activities. It’s no surprise that so many remain mired in abject poverty.

Yet, even in these dry areas, there is often water underground. Government agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have devoted vast resources to installing wells for needy populations in Africa, Asia and Latin America. These efforts, though earnest and well-motivated, often fail in the long term for a number of reasons.

• In arid regions, there may be ample water during the rainy season, but then the water table recedes during the dry months. Wells are often too shallow to reach this deeper water, so they become inactive.

The solution: drill deeper.

This is the strategy now being employed by city authorities in urban areas like Bangalore, India, where an exploding population has strained water resources to the limit. The older wells in the city were typically 300 feet deep. Now, newer wells reach depths of up to 1,500 feet to tap the hidden reserves. And for the time being, they’re meeting the city’s burgeoning needs.

This approach is also being used effectively by private relief agencies, such as GFA (SA) (GFA). Through Jesus Wells installed by its field partners, GFA has helped bring year-round water to many villages in South Asia, each well serving an average of 300 people. By drilling wells more than 600 feet down, villagers can access the deep water that was unreachable before. And GFA-supported Jesus Wells are built to last up to two decades.

In one Asian village, 15 families were relying on water from a polluted pond, convinced that a well would be impossible in their rocky hillside terrain. But through the intervention of a local GFA-supported pastor, workers drilled through the solid rock and found water. Most importantly, the workers didn’t stop there. They kept drilling to reach the deeper parts of the water table. That well now provides consistent water for the villagers even through the dry seasons.

• Another common problem has to do with well maintenance. Many well-intentioned organizations come into undeveloped areas and spend their time and money installing wells. But then they leave. The villagers often don’t know how to maintain the wells, so these valuable resources become useless. As a result, in Africa alone, an estimated 50,000 such projects now lie abandoned.3

The remedy is to bring local people into the projects from the start

so they feel an ownership stake, and then show them how to maintain the wells for the long term. In an effort to provide lasting solutions, GFA-supported field partners use local workers who use locally produced components to install the wells, and then they help train the villagers themselves to maintain the wells. As a result, those wells have stood the test of time. GFA-supported workers recently revisited one of their earliest well installations and were pleasantly surprised to find it still operational—20 years later. Because of that well, life in the village has changed dramatically.

As Saamel, one of the villagers, observes, “Now people don’t have to go to distant places to fetch water.”

Furthermore, the impact of a clean water well on Arnab and his family in Asia can be watched online.

Of course, that well has needed periodic maintenance during its 20 years of service. And when it did, the local villagers stepped up.

Saamel notes, “Whenever this Jesus Well breaks down or needs some maintenance or repair, people in this village contribute money and they actually get it fixed.” As a result, “There has been no time that this Jesus Well is not in use … people been using it ever since that was installed.”

More than 4,712

Jesus Wells have been installed by GFA (SA) in 2018 alone.

That marks a stark contrast to other wells in the area that provided foul-tasting water and eventually broke down. Now, Saamel observes, people from three nearby villages come to use the Jesus Well for its clean, reliable water.

“The water is very good and tasty and safe to drink,” he says. “So people don’t have to go to other water source, and they used this water for drinking and domestic chores, for giving to the cattle or whatever need they have, cleaning and washing; they used this water almost for everything. So, this well has been great help and great use for the entire villagers.”

As this story makes clear, encouraging people to invest in their own infrastructure is one key to making these lifesaving improvements sustainable. During 2018 alone, GFA (SA) helped install 4,712 Jesus Wells in villages all across Asia.

GFA (SA)’s clean water ministry is delivering pure drinking water to families all across South Asia through Jesus Wells, which are open to anyone in need, regardless of their ethnic or religious backgrounds. In this regard, Jesus Wells typically meet the urgent needs of poor families for clean water, rescuing their familes from waterborne diseases, poverty and even death.

Tapping Into the World’s Largest Reservoir

In his poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” Samuel Taylor Coleridge describes a crew of thirsty sailors stranded on the ocean. One of them utters these familiar lines:

Water, water everywhere,

Nor any drop to drink.

That’s an apt description of our world, in which people are desperate for water even though it covers 71 percent of the earth’s surface.4 Of course, most of it is in the oceans and not drinkable. Indeed, 97.5 percent of the earth’s water is saltwater.5 A person who drinks too much of it will die—ironically—of dehydration.

Granot desalination plant, Israel: Daslination here works by pushing saltwater into membranes containing microscopic pores. Photo by Mekorot Water Company (via IrishTimes.com)

However, visionaries have long hoped that someday we could harness the oceans’ vast water reserves for human use. That dream began to come true in 1881, when the first commercial desalination plant opened on the Mediterranean island of Malta. As methods improved during the 20th century, more plants opened in Europe, the United States and, especially, the Middle East. The desert kingdom of Saudi Arabia, oil-rich but water-poor, now produces more desalinated water than any other country. The nearby United Arab Emirates derives all of its drinking water from desalination. These countries are trading what they have—oil wealth—for what they desperately need—water. But in most of the world, the process has remained too costly to be a viable option.

A dramatic change occurred in 2005 when Israel opened its mega-capacity desalination plant in the coastal city of Ashkelon. This landmark achievement drastically lowered the cost of desalination while providing 13 percent of the country’s consumer water demand. Before, the country’s main sources of fresh water had been the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River that flows from it. But drought and overuse had depleted both resources to dangerously low levels. Israel had a strong motivation to find new, reliable sources of usable water. The Mediterranean Sea on its western border made desalination an obvious alternative.

After the success of the Ashkelon project, Israel launched another plant a few miles up the coast in Hadera in 2009. That was followed by the Sorek plant in 2013, which is currently the world’s largest desalination plant. Israel now uses desalinated water for more than half of its needs. The cost of that water—which had always been the major drawback of desalination—is now even lower. At about $30 per month per household,6 Israelis pay less for their water than many people in other developed countries.

There are numerous water-thirsty countries in Asia and Africa that border the oceans. They could all greatly benefit from this technology. Because desalination plants are expensive, it will be a challenge for poorer countries to develop them. But Israel has shown that desalination can be a viable, cost-effective solution.

Indeed, 97.5 percent of the earth’s water is saltwater. A person who drinks too much of it will die—ironically—of dehydration.

Another country that has made effective use of desalination is China. With a population of 1.4 billion—the world’s largest—China has enormous water needs. In recent years, millions of its people have clustered in the coastal cities, straining resources to the limit. That led to an intensive push for alternative water sources. China began exploring desalination in the 1950s and now has more than 139 plants.7

With the inexorable growth of industry and populations around the world, the demand for water will only increase. And given the limits inherent in other sources, the desalination option will become indispensable. Meanwhile, advances in technology are making it available to more people than ever.

The Ashkelon desalination facility along the Mediterranean Sea in Israel, is one of the largest in the world, and is one of five plants providing Israelis with 65 percent of their drinking water.

Photo by IDE Technologies Ltd., (via TimesofIstrael.com)

Filters Make Contaminated Water Safe

In much of the world, people rely on surface water for drinking and washing. But that water often contains dangerous toxins or pathogens. In those cases, people face the difficult choice of choosing between drinking tainted water and going thirsty.

One of the most common—and deadly—symptoms of waterborne diseases is diarrhea. It kills millions of people every year, most of them in Africa and South Asia. Children, being especially vulnerable, suffer the worst. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2,195 children die of diarrheal diseases every day.8 Other waterborne illnesses include polio, tetanus, typhoid fever, cholera, dysentery and hepatitis A.

Waterborne illnesses are prevalent in Asia, but when dirty water is cleaned and purified through BioSand water filters, diseases can be prevented.

The tragedy is that such diseases can be easy to prevent. One study showed that the incidence of diarrhea can be reduced by 40 percent if people simply wash their hands regularly with soap.9

Another effective weapon against disease is amazingly simple and affordable: a BioSand water filter, which costs just $30 and is small and portable enough to fit in any home. It removes most of the contaminants in water, making it 98 percent pure. With just one BioSand water filter, an entire family can enjoy clean water for as long as 20 years. GFA (SA) has been partnering to provide BioSand water filters to Asian families since 2008, distributing more than 73,500 so far. And the results have been dramatic.

73,500 BioSand Water Filters

have been provided by GFA (SA) to Asian families since 2008.

Nirmala’s story is typical and illustrates the impact these simple devices can make. She lives in a small Asian village where the only water source is a small polluted pond.

“Since we drank from the pond on a daily basis,” Nirmala says, “we were frequently contracting diseases and stomach problems. Our symptoms ranged from headaches to skin problems to internal pain. It was a very painful and discouraging way to live.”

Then, a GFA-supported worker visited Nirmala’s village and told her about the difference a BioSand water filter could make.

“A team soon came and installed a filter in my home,” she says. “My family and I were so happy to receive such an amazing gift.”

Now, health has returned to Nirmala’s family. And an entire village is being transformed.

No electricity or batteries are needed for a BioSand water filter like this one. Through natural ways of killing harmful bacteria, these effective filters turn dirty water sources into pure, fresh drinking water. Women like these, and their children and families, who were sick and even dying from waterborne illnesses are now regaining their strength, health and well-being through the clean water they are able to drink from BioSand filters.

A Better Future is Possible

These accounts show what is possible when goodwill and knowledge combine. But they also remind us that the world water crisis is far from being solved.

The United Nations has described concrete objectives for defeating the world’s water problems in its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Among other things, the participating member states committed to “end poverty in all its forms” and “shift the world on to a sustainable and resilient path.”10 But so far, the world is “off track” in achieving those objectives,11 according to the UN’s Synthesis Report 2018 on Water and Sanitation. The report states that, to be more effective, efforts must address issues of “weak funding, planning, capacity and governance of water and sanitation services as a top priority.”

But as the villagers depicted in this article demonstrate, the best solutions don’t always come from top-down efforts imposed from outside. Rather, they arise from cooperative efforts that involve local residents in the construction, maintenance and acceptance of their own sustainable solutions. Relief agencies that respect the dignity and freedom of the people they serve offer the best hope for success.

If you’d like to make a personal impact on the world water crisis, consider giving a needy family a simple BioSand water filter. For only $30, GFA (SA)’s field partners can manufacture and distribute one of these effective filters to a water-compromised family in Asia and provide them with clean, safe water. Other NGOs that are making a difference in regard to the world water crisis include water.org, which makes microloans to families to install clean water solutions in their homes, and Charity: Water, which partners with organizations worldwide to provide safe water solutions to the 10 percent of the world’s population that lacks access to clean water.

Together, we can end the world’s water crisis.

Men like these help build BioSand water filters for countless families in Asia. They start by pouring wet cement into these metal molds and go from there. These filters require no electricity to use, yet they make water almost as pure as bottled water!

This ends the update to our original Special Report, which is featured in its entirety below.

Dying of Thirst:

The Global Water CrisisThe Crucial Quest for Access to Clean Water

The statistics are mind-numbing.

- 502,000 people die each year from diarrhea—caused by unsafe drinking water.12

- 2.1 billion people have no access to safely managed drinking water.13

- 159 million people get their drinking water directly from surface water sources.14

- 263 million must travel more than 30 minutes daily to collect their water.15

Safe drinking water is something most of us take for granted. But for millions of people, the only water they have is contaminated. And millions more are at risk of having no water at all. According to the United Nations, 1.9 billion people (27 percent of the world’s population) live in “potentially severely water-scarce” areas.16

They wake up each morning knowing they must fight to survive.

For those of us who enjoy ready access to clean water, these numbers are difficult to grasp. But for the individuals they represent, life is simple: They wake up each morning knowing they must fight to survive. The day might begin with a long journey to a watering hole. Everything else depends on that crucial task. For others, the day begins and ends in wretched poverty—because chronic illness prevents them from working. And for some, a normal day means watching their children die slowly from waterborne disease.

This is the heartbreaking reality for people around the globe. The widespread lack of clean water is a crisis we can’t ignore. But to address it, we must understand it.

Why Water Is So Crucial

Water comprises about 60 percent of every human body. It’s essential to the functioning of our cells. And when we don’t take in enough water, things go wrong very fast. We can survive for weeks without food, but without water, we last only a few days.

When acute dehydration sets in, we feel thirsty; then we can begin to experience headaches, dizziness, muscle cramps and rapid heartbeat. If we don’t receive water in time, we may drift into a quiet sleep—and then death. The effects of chronic dehydration can be less dramatic but just as insidious. Over time, the skin may become dry and flaky. Constant fatigue and muscle weakness make it impossible to function normally.

A lack of clean water affects every imaginable area of life

Another cruel fact of life for millions is that the water they do have is contaminated with microbes or deadly trace elements. They can choose to go thirsty—or drink water that makes them sick.

To stay healthy, we need to drink about a half-gallon of water each day. But of course, we need water for more than drinking. We use it to wash our clothes and our bodies. We need it to care for our livestock and to irrigate our crops. So a lack of clean water affects every imaginable area of life. Overall, we need between 13 to 26 gallons to perform all our daily tasks.

Access to safe water is also a key to economic well-being. Farmers need a steady supply of water for their livelihood. If there are no reservoirs to draw from, they must rely on the rain. So when drought hits, the effects can be catastrophic—for the farmers and their entire communities.

People crippled with waterborne disease often spend most of their money and time dealing with it. Work, education and other activities that might help them prosper must be put on hold. Considering all these factors, it’s no wonder that the places with least access to safe water are also among the poorest.

During her school break, 9-year-old Sulem Hire from Ethiopia carries jerry cans to collect water at a borehole four kilometers from her home. This means an eight kilometer walk carrying heavy jugs of water—a heavy task for a young girl. Photo by Mulugeta Ayene, UNICEF

Plentiful—Yet Scarce

There’s enough water on earth to fill 326 million cubic miles (or 1.36 billion cubic kilometers).17 In fact, 71 percent of the earth’s surface is covered with water.18 So why is water still so scarce for so many people?

96.5%

of the earth's surface water is contained in the oceans.

To start with, 96.5 percent of the earth’s surface water is contained in the oceans.19 And of course, its salt content makes it useless for drinking. Desalination can make saltwater drinkable, but the high cost of that process has put it out of reach for most of the world—so far.

Of the earth’s freshwater, 68.7 percent is locked away in ice caps, glaciers and permanent snow. Another 30.1 percent is in the ground.20 That leaves only a tiny fraction available as usable surface water, which comprises 78 percent of the water we use. The source of that surface water is the oceans. When water evaporates from the ocean surface, it leaves its salt content behind, and some of it then reaches the earth as precipitation—mainly, rainfall. That water then flows through our rivers and streams and collects in lakes and ponds. We depend on that runoff for most of our water needs.

But geographic and atmospheric conditions can prevent the rain from reaching some places. About 40 percent of the earth’s land mass is considered arid or semi-arid. And together, those areas receive only about 2 percent of the earth’s water runoff.21 As a result, people who live in those regions often face chronic water shortages and a constant struggle to find adequate water. They typically rely on wells that tap the water in the ground. But when those wells fail, disaster follows quickly.

Digging Deep to Find Water

In some arid and semi-arid regions, people depend on wells that provide water during the rainy season but go dry when the rain stops. There may be more water available deep in the ground, but the wells are too shallow to reach it. GFA (SA) (GFA) has recognized this problem and has helped solve it by helping to drill wells up to 600 feet deep. The people can then rely on those wells for water all year round.

Local labour and materials are used to drill Jesus Wells, which keeps costs low.

Nirdhar and Karishma’s village sits on a rocky hillside in Asia where, for years, the only water source was the rainwater that collected in a pond. In the dry months, the pond was unreliable, so the villagers would buy water from a visiting tanker truck. GFA-supported pastor Dayal Prasad was aware of the problem and asked his leaders if it might be possible to drill a well for the villagers.

Through the generous donations of GFA supporters around the world, the well project began. But it was risky; the land was notoriously dry. Few local people believed a well was even feasible. The team drilled deeper and deeper into the hard rock terrain with no results. The effort seemed futile. And then, at last—they struck water.

But the team didn’t stop. They drilled even deeper so the villagers would be assured of water through the dry months. And now, they have clean water year-round for drinking, cooking and bathing.

“We never thought a well would be drilled in our village,” Nidhar confides. “But the true need of this village was met by GFA (SA). We are truly thankful for it.”

Twin Hazards: Drought and Flooding

Even places accustomed to adequate rainfall can be vulnerable to drought, which may come without warning. Its impact usually depends on the preparations people have made beforehand. Most of the developed world has systems and infrastructure in place to mitigate a drought’s worst effects. In 2018, Washington state and areas of the American Southwest experienced a severe drought, which caused hardship but no large-scale human catastrophe. But it’s a different story when drought strikes poor areas that are already struggling. People die of dehydration. Crops fail and famine follows. Economies are devastated.

Drought is a terrible affliction, but the opposite problem can also occur, and sometimes in the very same places—too much water at once.

People die of dehydration. Crops fail and famine follows.

Economies are devastated.

Many communities in arid regions are physically unprepared for floods, which often come suddenly. And a lack of groundcover in the desert can make the flooding even more destructive. Floodwaters often mingle with raw sewage, which can cause skin rashes, tetanus, gastrointestinal illnesses and wound infections in people exposed to it. The standing water left behind by floods also breeds mosquitoes, which transmit vector-borne diseases such as dengue, malaria and West Nile fever. In some places, rodents proliferate after flooding. These creatures carry microbes such as leptospira bacteria, which are then released in the rodents’ urine. As a result, leptospirosis can reach epidemic levels after a flood. Left untreated, it can cause respiratory distress, liver failure and death.

A mother cares for her son who is being treated for cholera at a UNICEF-supported cholera treatment center in Baidoa, Somalia Photo by Mackenzie Knowles-Coursin, UNICEF

Waterborne Diseases

Even under normal conditions, people in many regions are exposed to life-threatening diseases from their water, including typhoid, polio and hepatitis A. Among the most common waterborne diseases is diarrhea, which can be caused by any of several pathogens. It kills about 1.5 million children every year, more than 80 percent of them in Africa and South Asia. World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 88 percent of those deaths are caused by unsafe water, inadequate sanitation, and poor hygiene.22 Diarrheal diseases kill by depleting the body’s fluids, often very rapidly.

Children are most vulnerable because their metabolisms use more water than adults’, and their body weight consists of more water proportionally than an adult’s. Their kidneys are also less able to conserve water.23

Diseases that are so deadly can be prevented with changes that are simple.

Children with malnutrition and weakened immune systems are especially susceptible to the worst effects of diarrhea. This explains why diarrheal disease is one of the primary killers in poorer countries but not in the developed world. Some diarrheal diseases target adults and older children. One of the most familiar and deadly of these is cholera, which afflicts between 1.4 million and 4 million people each year, killing thousands.24

In some documented cases, improving the quality of water at the source, combined with treatment of household water and safe water-storage systems, has reduced the incidence of diarrhea by 47 percent. And studies show that simply handwashing with soap can reduce the incidence by 40 percent.25 These figures underscore a tragic truth: Diseases that are so deadly can be prevented with changes that are simple.

Trace Element Contamination

Sometimes it isn’t living organisms that make people sick, but it’s the naturally occurring elements in the water. Heavy metals and other trace elements are usually present in our diets, and in fact, many of them are essential—but only in tiny quantities. When we ingest more than the safe levels, we can experience illness and even death.

In 2014, four Jesus Wells were dug by GFA (SA)-supported workers in one drought stricken region—now approximately 5,300 people benefit from these wells. Read the story »

Some of these elements are in the ground and leach naturally into the water we use, while others are introduced into the water supply through industry, mining and agriculture.

This was the problem facing four Asian villages when GFA-supported workers came to the scene in 2014. This area typically experienced several months of drought, followed by heavy monsoon rains. But the water left by the rains was contaminated with chemicals. Villagers with enough money could buy their own water, but the poor had to walk long distances every day to ask for water from local landlords. GFA-supported pastors in the area arranged for wells to be installed in all four villages, bringing clean water at last to approximately 5,300 people.

One of the most well-known water contaminants is lead. Lead poisoning can cause headaches, abdominal pain, mood disorders, high blood pressure, joint and muscle pain, and difficulty with memory or concentration. As always, children experience the worst effects. Lead poisoning can delay their development and cause learning difficulties. They may also experience fatigue, vomiting, hearing loss and seizures.

Water is a fragile resource, and its problems are not limited to the developing world.Since lead paint was identified as a major problem in the United States during the 1970s, a concerted national campaign reduced its impact over time. But Americans received a wake-up call in 2014 when the water supply in Flint, Michigan, came under scrutiny—as described by Karen Burton Mains in GFA’s special report “The Global Clean Water Crisis: Finding Solutions to Humanity’s Need for Pure, Safe Water.”26 Residents complained about the color, taste and smell of their water. It turned out that the service lines from water mains to individual homes in Flint were made of lead and were not treated with corrosion inhibitors, which keep the contamination at acceptable levels. Eighty-seven cases of Legionnaire’s disease were associated with the contaminated water, leading to 12 deaths. Overall, more than 100,000 people had been exposed to a dangerous poison. The Flint saga reminded everyone that water is a fragile resource, and its problems are not limited to the developing world.

The National Guard delivers bottled water to residents of Flint, MI.

By Linda Parton/Shutterstock.com

A Simple Solution

People in the developed world rely on their water providers to protect them from such threats. For those who can afford it, a home filtration system offers added security. But people living in poorer areas have no such protection. They often collect their water from fetid ponds or polluted streams. They’re exposed to all the worst dangers that may be hidden in their water.

Fortunately, a solution exists that can offer them protection similar to what the rest of us enjoy. And it’s amazingly simple, portable, effective and affordable. It’s called a BioSand water filter.

“Since [the Biosand water filters] were installed, all water-caused and waterborne diseases have ceased.”

BioSand water filters use mechanical and biological processes to remove heavy metals, bacteria, viruses, protozoa and other impurities from water. They are widely recognized as effective and are small enough to fit easily in virtually any home. Most importantly, they are inexpensive—just $30 for a filter that can serve an entire family with clean water for decades. Seeing the dramatic impact BioSand water filters have, GFA-supported workers have built and provided more than 73,500 of them for Asian families since 2008.

Members of this family suffered from waterborne illnesses, but now they—and their neighbors—are benefitting from a simple-to-use BioSand water filter.

Aanjay, a farmer in Asia, saw firsthand the effects of contaminated water on his family and his entire village.

“We were forced to use dirty and filthy water for cooking and drinking,” he recalls. “Thus, we suffered stomachache, jaundice, typhoid and diarrhea.”

The villagers also had to use the tainted water for bathing, which caused skin infections.

That changed when some GFA-supported pastors provided BioSand water filters for Aanjay’s family and several others.

“Along with receiving a filter, families also received health and hygiene training that works to significantly lower the incidence of waterborne illness,” Aanjay says. “Now the villagers are getting purely filtered water for drinking. Since [the Biosand water filters] were installed, all water-caused and waterborne diseases have ceased.”

Two young boys towing a can of water in the slums of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, in order to distribute water to the inhabitants.

By MattLphotography/Shutterstock.com

Burkina Faso: Africa’s Anguish

Recurring drought, contamination and lack of funds have all contributed to Africa’s severe water problems. A vivid example of all three can be found in the little landlocked country of Burkina Faso.

Located in the vast savanna region south of the Sahara Desert, Burkina Faso endures up to eight months of dry weather each year.29 When drought makes conditions even worse, as it did in 2016, a true crisis occurs. That year, the capital, Ougadougou, was able to provide only intermittent water service for its 2 million residents. People were forced to travel far into the countryside to find usable water.30 Water shortages like this, and the power outages that accompany them, have become a normal part of life for city residents.

Nearly half the residents of Burkina Faso live without clean water.

For people in rural areas, the hardships are even worse. Eighty percent of Burkina Faso’s people are subsistence farmers,31 so droughts are especially devastating for them. The country is also plagued by waterborne diseases common to undeveloped areas—diarrhea, hepatitis A and typhoid fever.32

According to Water Aid UK, 4,500 children under the age of 5 die of diarrhea each year in Burkina Faso, and nearly half the residents live without clean water.33 When the rains do come, mosquitoes that breed in the standing water spread malaria, yellow fever and dengue fever.

These women are collecting water for crop irrigation in Burkina Faso, where the water crisis is severe.

By Gilles Paire/Shutterstock.com

One of the main industries in Burkina Faso is gold mining. But the mining process has introduced deadly arsenic into the groundwater.34 On top of all these challenges, the rapidly-growing population is putting unprecedented stress on the water supply. War and disruption in neighboring countries have displaced millions of people, many of whom seek refuge in Burkina Faso. This has only exacerbated a problem that was already severe.35

Efforts to improve conditions in Burkina Faso haven’t always been effective. Relief workers from Water Aid UK found that many existing wells there were unusable because of broken handpumps. And toilets provided by the government to improve hygiene were going unused—because people don’t know what to do with them.36 This underscores the importance of education to go along with physical improvements. One without the other leads to failure.

Against this stark backdrop, a number of entities are working valiantly to reverse the cycle of despair in Burkina Faso. Since 2000, the government has taken real steps to address the crisis, creating five water basin committees to protect and preserve water resources throughout the country.37 Meanwhile, many non-governmental organizations are helping by drilling new wells, repairing old ones and training local people to manage their water effectively. Among these are the aforementioned Water Aid UK, Myra’s Wells, SIM missionary organization, The Water Project, Hearts for Burkina, Engage Burkina, and Living Water International.

India: Success and Challenge

In recent decades, India has emerged as a global economic powerhouse. It is now the seventh-largest economy in the world by nominal gross domestic product (GDP)38 and at least the fourth largest in purchasing power parity.39 Much of this success stems from the technology field, India’s fastest-growing sector. Information technology, process outsourcing and software services are among the country’s booming industries.

India is suffering the worst water crisis in its history.

But success is accompanied by great challenges. India is home to about 1.34 billion people and is still growing. Its population, now the world’s second largest,40 is projected to overtake China’s as early as 2024.41 This has placed unprecedented stress on the country’s water resources, which are already stretched to meet the needs of a growing population.

In June 2018, the Indian think tank NITI Aayog released a comprehensive report on India’s water status. Among its conclusions:

- India is suffering the worst water crisis in its history.42

- 200,000 Indians die each year from lack of clean water.43

- 600 million Indians face high-to-extreme water stress.44

- By 2020, 21 cities could completely run out of groundwater.45

- By 2030, the country’s water demand is projected to be twice the supply.46

The booming cities have borne a large portion of India’s water stress. Bangalore, known by some as India’s Silicon Valley, is a good example. The city’s needs were once met by wells that reached 300 feet deep. But now, 400 bore wells must go down as far as 1,500 feet to find water. How long will that suffice? No one knows.

In this remote village, a Jesus Well provides clean, safe water to many families. Each Jesus Well serves an average of 300 people for about 20 years, and the wells may be drilled up to 600 feet deep, providing pure water in even the worst droughts.

In the countryside, the challenges are different but just as dire. Agriculture uses some 80 percent of India’s water.47 When water is unavailable, the farmers feel it immediately. They can quickly lose their livelihoods.

Meanwhile, millions of Indians have no reliable access to water at all.

Much of India is arid or semi-arid. Vast areas receive rain only sporadically from storms brought by the summer monsoons. Many people collect their water from surface sources, which are often contaminated. The daily trek to a local pond is a regular feature of life for many rural Indians. They may walk for hours just to obtain their day’s supply of water. That leaves little time to work productively or improve their lives.

For years, Gospel for Asia (GFA) has been helping to equip national workers to get wells installed in needy communities. They’re called Jesus Wells and are fitted with a plaque sharing Christ’s words to the Samaritan woman: “Whoever drinks of this water will thirst again, but whoever drinks of the water that I shall give him will never thirst. But the water that I shall give him will become in him a fountain of water springing up into everlasting life” (John 4:13–14).

Israel: A Glimpse into the Future

While discussions of global water issues typically focus on the problems, it’s also helpful to consider the success stories. One of those is the tiny state of Israel.

After World War I, the territory of Palestine came under the control of the United Kingdom. As the British government was considering what to do with this important strip of land, its economists concluded that the area’s water resources could only support about 2 million people.48 There were slightly more than 800,000 residents there at the time. But after the modern state of Israel was created in 1948, that number nearly doubled in just three years—and kept climbing.49 Today, Israel is home to more than 8 million people,50 with another 2.8 million in the West Bank51 and 1.8 million in the Gaza Strip.52

Clearly, a drastic program was needed to meet the water demands of this booming population. Through the efforts of visionaries such as water engineer Simcha Blass, Israel not only met this challenge but became an exporter of water technology, water-intensive crops—and water itself. The story of that success can serve as a model and inspiration for other countries.

Israel points the way to a future free from water insecurity.

Simcha Blass, an Israeli visionary in the clean water field.

Photo by Ybact on Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 3.0

Israel’s leaders realized that all those new immigrants would need to eat, so food production became an urgent priority. The Negev in the south of Israel was a vast dry desert where few people lived. But Simcha Blass was convinced there was water underground that could be accessed through deep drilling. He was right. That was the beginning of an agricultural boom in one of the world’s most inhospitable environments. Some people saw it as a fulfillment of the prophecy in the book of Isaiah: “The desert and the parched land will be glad; the wilderness will rejoice and blossom” (Isaiah 35:1 niv).

Blass also envisioned pipelines that would stretch from the water-rich north of Israel to the south where water was most needed. Through years of effort, his visions became reality.

Israel’s visionaries then turned their sights to the world’s most abundant water source—the oceans. The idea of processing seawater for drinking and agriculture has long been an elusive dream for people around the world. Israeli scientists experimented with several desalination techniques, most of which proved too costly to be practical. But with perseverance, Israel developed a system which, though still expensive, provides an important supplement to its other water sources. Israel now has several functioning desalination plants on its Mediterranean coast, which provide an astonishing 27 percent of the country’s water.53 Most importantly, the desalination plants serve as a kind of insurance policy against severe droughts and other disruptions. The ocean, after all, is always there.

Drilling for water in Qumeran Valley, Israel

Photo by Tamarah on Wikimedia / CC BY-SA 2.5

Reclaimed waste water is another promising source of water for agriculture that Israel has used effectively. The idea of reusing sewage is repulsive to most people, but when water is at a premium, as in Israel, it’s an option that can’t be ignored. The main concern with recycled waste water is that dangerous microbes or other contaminants might remain even after processing. That could endanger anyone exposed to it, as well as the crops treated with it and the groundwater under the crops. Israel addressed this risk with a process that resembles a giant version of the BioSand water filters described earlier.

Israel’s sewage treatment plants were located near some sand dunes, under which there was a known water aquifer. The water engineers began speculating: What if the treated waste water were released into the sand and allowed to percolate down into the groundwater? Would the sand act as an effective filter? It was a risky experiment, but worth trying. After more than a year, the results were in. Yes, the sand made the water clean, safe enough for agricultural use. Today, Israel reuses more than 85 percent of its sewage, which provides 21 percent of its water.54

Israel also pioneered the use of drip irrigation, which made it possible to grow abundant crops by using limited water supplies efficiently.

These innovations may seem out of reach for many developing countries. Their implementation would require concerted, long-term effort, and they can be expensive. But they show what is possible. These are things we know can be done—because they have been done. They point the way to a future free from water insecurity. And that’s something all people can aspire to.

Internally Displaced People fill containers with water at a tap inside the Dalori camp in Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria.

Photo by Ashley Gilbertson VII Photo, UNICEF

The Big Picture

The world’s need for water has only accelerated with the inexorable growth in population, which could reach another 2 billion by 2050. And by then the demand for water could increase by 30 percent.55

March 22

is World Water Day.